Let’s spill the tea on the world’s favorite beverage.

I’ll start things off with a primer of some tea basics. This is by no means exhaustive, and I hope leaves (ha!) plenty of room for discussion.

Note: most of my tea knowledge comes from the “loose leaf” premium realm of imported teas, so much of what I present here is filtered through that lens. I do not have anything against teabags or flavored teas, they’re just not my “cup of tea”. Sorry for that joke.

1. What is tea?

(I’ll keep this section brief, as much of it is common knowledge)

Some regions call it tea or tí. Others call it cha or chai. But what is it?

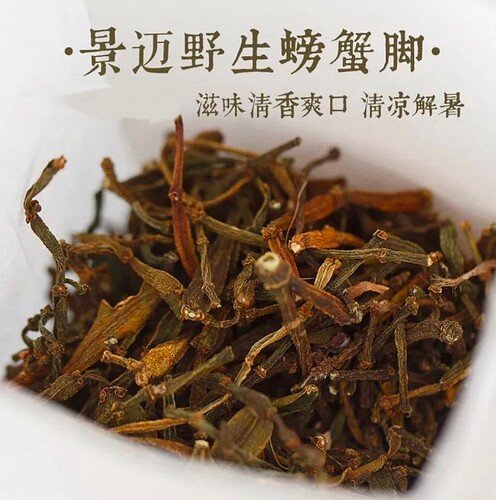

Tea generally refers to one partocular species of plant, indigenous to China, camellia sinensis, colloquially known as the tea plant, tea shrub, tea bush, or tea tree. Less commonly, another species of the camellia genus, camellia taliensis, or the “wild tea bush”, is also used.

The leaves (and sometimes stems) of these plants can brewed in water to create the infusion we call tea.

The beverage produced by brewing tea leaves is generally served hot (but sometimes iced) and is often considered refreshing or revitalizing (Tea naturally contains the stimulant compound, caffeine).

Subsection: What is NOT tea?

Infusions made with other plant matter are tisanes, and separate from tea. Common tisanes include chamomile, lemongrass, yerba maté, mint, hibiscus, and various fruits. These often go by the term “Herbal Tea”, but they are as much tea as peanut butter is a dairy product.

Rooibos sometimes goes by the name “Red Tea” in Africa and the West, but it is also not tea.

It goes without saying that coffee is not tea.

Rarely, the flowers of camellia sinensis are also used to make “tea flower tea”. This can be considered a type of tea or a type of tisane, and is up for debate.

2. Tea terminology

“Tea” (or “cha”) refers to the plant, the leaves, and the beverage. In order to differentiate between the leaves and the beverage when discussing brewing, the resultant liquid is often referred to as “soup” or “liquor”

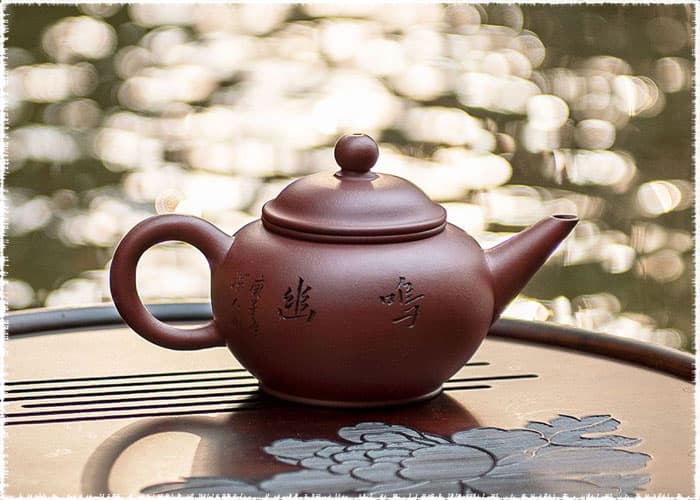

“Teapot” or “pot” refers to a vessel in which the tea is brewed. This is sometimes confused with “kettle”, which is a vessel in which water is heated before being poured into the teapot.

“Teacup” or “cup” refers to a drinking vessel which contains the tea. In Southeast Asia, most traditional teacups have no handle, and are used filled only partway so that the user can hold it by the rim without burning their fingers. In British-influenced areas, teacups are often dainty, decorated, abd have a small handle. They are also often accompanied by a saucer, a small dish which acts as a coaster, a plate, and a spill-catcher.

A “Teabag” is a small pouch, made of filter paper or mesh, which contains dry tea leaves this is used as a portable way to brew single-servings of tea (or multpliple servings with a large bag or multiple bags in a tea pot.)

“Loose leaf” refers to tea leaves that do not come in a bag. These are often whole leaves or large pieces, and are considered a premium product when compared to bagged teas.

A “gaiwan” is a small teapot designed to produce a single cup of tea. It is usually a small, circular cup with a lid and saucer. It is designed to be poured with one hand. Gaiwans are popular in China and Japan.

“Tea ceremony” is a brewing style of tea, as well as a ritual. This ritual usually involves multiple vessels, usually including a vessel to heat the water (such as a kettle), a teapot or gaiwan, a “chai hai”, which is a serving vessel the tea liquor is strained into, and cups for drinking. Sometimes, an “aroma cup” is also used.

An “aroma cup” is a narrow tra cup which is not meant for drinking. As part of the tea ceremony, tea can be poured from the chai hai into the aroma cups, and from there into the drinking cups. The participants can then smell the concentrated tea steam before taking their first sip.

A “tea tray” is a tray, usually with a drainage pan undernreath to catch excess liquid, which is used as a platform for the tea ceremony.

A “tea pet” is a small clay figurine. The tea rinse is often poured on these teapets during a tea ceremony, and over time, they absorb the coloration and aromas of tea.

There are many more ceremonial items that we can get into later.

3. Health Benefits of Tea

I try not to get into tea as a health food, as there is conflicting research, and a whole world of false claims. Tea does contain antioxidants, fluorine, and caffeine, all of which can have beneficial effects under some circumstances. It can often also contain pesticides, heavy metals, radiation, and (in some bagged teas) microplastics.

I’ll leave it at that.

4. Types of tea

Note: Tea has a long history, and much of it, especially for the west, is tied up with British colonialism. Some of the terminology is still tainted with colonial names, but I try to do my best to point that out as it arises. I will also try to use Chinese names and terms where appropriate. Knowing these can be helpful when navigating the catalogs of some Chinese teasellers.

First off, tea is generally separated into categories by the types of processing and/or amount of oxidation the leaves undergo. Oxidation is a process in which tea levaes are exposed to the air. This causes the leaves to darken, dry and changes the flavor (and strength) of the tea. The oxidation process makes much of the caffeine in tea leaves more readily available for infusion. Paradoxically, unoxidized tea leaves contain more caffeine, but tea made from oxidized leaves contains more caffeine, as much of the caffeine stays in the unoxidized leaf.

I will try to list the major (and one minor) types in order from least to most processed. Note: there are many exceptions and difficult to categorize teas. This is not a hard and fast set of rules, but more like a group of guidelines.

White Tea or “bai cha”, is made of tea leaves which are wilted and dried (sometimes sun-dried). White tea is not rolled or oxidized. White teas tend to be lighter in taste, liquor color, and caffeine content. They are very high in antioxidants. White teas mostly come from China. Some representative varieties are Silver Needle (baihao yinzhen) and White Peony (bai mu tan).

Green Tea or “lu cha”, is also minimally processed, but Green teas are usually heated to fix the natural chlorophyll and retain their green color. This is often done by charcoal-firing, pan-firing, oven-drying, or steaming. The teas are then usually rolled (and sometimes formed into shaped) before drying. Green tea is not oxidized, Green teas often have a fresh, vegetal or grassy taste, and yellow or green liquor. They are lower in caffeine than black teas, but higher than white. Many varieties of green tea are produced in China and Japan. Some notable Chinese examples include Green Snail (bi lo chun), Dragonwell (long jing), and Gunpowder (zhu cha), which is a smoky green tea rolled into small pellets. Chinese green tea is sometimes mixes with dried jasmine flowers in Jasmine Tea (molihua cha). Some notable Japanese examples of green tea are Sencha and Gyokuro, which are grown for exceptional chlorophyll content (especially Gyokuro) to produce a bright green tea soup, Hojicha, which is roasted in a procelain pot to a golden yellow color, and Kukicha, which includes many tea stems which make the tea taste bright and sweet. A traditional Japanese green tea blend involves a mix of green tea and toasted rice, to make a toasty tea called Genmaicha.

Yellow Tea or “huang cha”, is a rarity, and sometimes lumped in with green teas. Yellow tea is produced in much the same way as green tea, but after heat-fixing, the leaves are piled and “sweltered” in which they undergo light fermentation before being rolled and dried. Yellow teas share a lot ofcharacteristics with green teas, but tend to have a more golden color, and often the grassiness of the flavour is removed, in exchange for something a bit richer and sweeter. Yellow teas tend to be rare, expensive, and hard to find. They are primarily produced in China. Some examples include Jun Shan YinZhen, and Huo Shan Huang Ya.

Note: In Korea, they also have something called “Hwangcha” or yellow tea, but by traditional categorization, this is an Oolong.

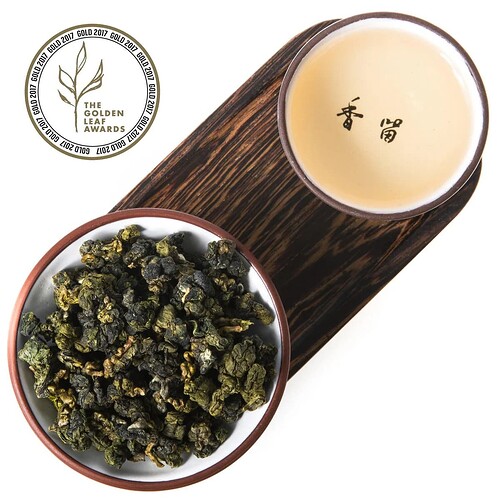

Oolong Tea or “wulong cha”, is made from leaves that are partially oxidized before heating, rolling, drying, and firing. Among the different types of teas, Oolong teas have the most variety. Some oolong teas are barely oxidized, making them similar to green teas. Others are nearly fully-oxidized and resemble black teas. A great many fall somewhere in between. Oolongs range from light and floral to full-bodied and roasty to dark and minerally. Traditional oolongs mostly come from China and Taiwan (though other nations such as India, Japan, and South Korea also produce them). Some representative Chinese oolongs include Iron Goddess Tea (tie guan yin), which is traditionally light and floral, but is also readily available in roasted varieties, Phoenix Mountain (dan cong), which is sweet and astringent with fruity and floral notes, and Big Red Robe (da hong pao) which is a type of “Wuyi rock tea” with a distinctive mineral flavor. Taiwanese oolongs, often referred to as “Formosa teas” due to the lingering influence of imperialism. Some representative Taiwanese oolongs include Oriental Beauty (dongfang meiren) is a heavily-oxidized tea (with a name also tinged with western bigotry) with floral notes, and Ali Shan is a jade oolong that tastes of honey. Many westerners are only familiar with oolong as one flavor of tea, the “oolong tea” sold in teabags, which is often in the style of Dongfang Meiren.

Black Tea or “hong cha”, is tea that is fully oxidized. Many lower grade teas accelerate the oxidzation process with a method known as CTC (crush, tear, curl). Black tea is higher in caffeine and richer in flavor. Much black tea is produced in India, China, and Sri Lanka. Much of what you find in teabags like Lipton or Twinings is Ceylon tea, from Sri Lanka, made using CTC methods (the word Ceylon is another remnant of the British Empire). In China, black teas are called “red tea”, as they refer to something else as “black tea” (see below). Indian teas are generally divided by the estates on which they are grown rather than by a wide range of styles.

Indian black teas traditionally fall into two categories: Assam and Darjeeling. Assam teas are rich and malty. One popular blending is Assam tea with oil from the bergamot citrus, which is called “Earl Grey”. For Darjeelings, see below. Some representative Chinese black teas include Golden Pekoe (feng qing) from the Yunnan province, the perported birthplace of tea, Fuzzy Eyebrow (jin jun mei) from the Fujian province, and Golden Monkey (jin hou cha).

Darjeeling tea is a special case. Unlike the above teas, the leaves in Darjeeling are not processed uniformly. Though Darjeeling is usually considered a type of black tea, it is more like a blend of fully oxidized black tea leaves with less-oxidized or unoxidized leaves. This creates a tea that is more delicate, astringent, and difficult to brew than other black teas, and that is known to have a distinctive “muscatel” wine-like tasting note.

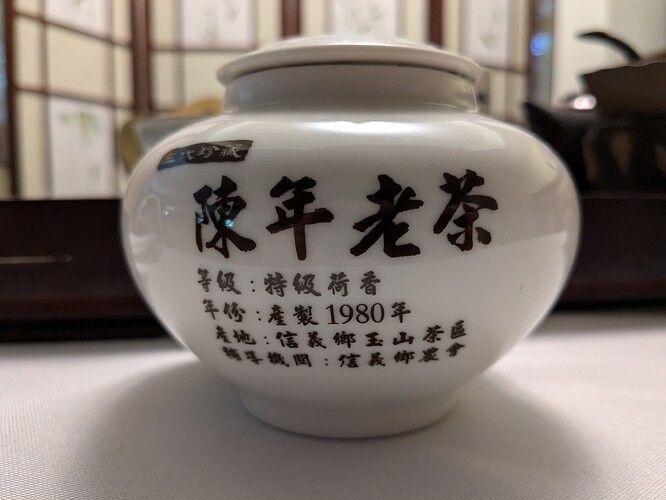

Dark Tea (Post-fermented tea) or “hei cha”, is relatively new to the west, but has a long history in China. These teas are fermented after drying either through aging or wet-piling. By far the most prominent hei cha is puerh, to the point where dark teas are just referred to as "puerh when categorizing, but there are others, such as liu bao which is inoculated with the “gol;den flowers” probiotic fungus, erotium cristatum. Aged (or aging puerh is called “raw” puerh (sheng puerh) and pile-fermented puerh is called “ripe” puerh (shou puerh). Generally, both get better with age, but sheng puerhs are much less drinkable when young, but improve well beyond shou puerhs when given sufficient age. These teas are usually packed tightly into 500 gram cakes called “bings”, though are also sold in smaller cakes or single-cup coins. Dark teas usually brew a very dark thick liquid with ruby hints. Some sheng puerhs can brew up quite a bit lighter in color though.

Lastly, I should also mention Purple Tea. Purple tea is not a specific style of tea, but rather, leaves from a tea plant with a mutation causing the leaves to grow purple in color. Purple tea is higher in antioxidants and can be made into any style of tea. My opinion is that they don’t taste as good as traditional teas and they’re a gimmick, but ymmv.

Later, we’ll get into teawares, brewing methods, and places to buy teas!