30/30 Sega Saturn Portable

30/30 Sega Saturn Portable

We’re living in a kind of Golden Age for the Saturn’s rehabilitation. After years of hardship, emulation has made prodigious leaps with SSF, Yabause and the Zebra Engine. On Nintendo Switch, you’ll now find some twenty Saturn games officially released (without a single one coming from Sega) via direct emulation, the surrogate emulation of a later port, or a proper HD remastering or full remake of their own.

The console’s draconian security was finally circumvented in 2020, allowing new solutions such as Saroo, Fenrir and Satiator to flourish. New amateur translation projects appear frequently for various languages, sometimes with titanic projects like the famous Bulk Slash patch. We are eating good, as kids say these days.

But let’s go back two decades. Ten years after the Saturn, almost day-for-day, came the Nintendo DS and PlayStation Portable. You were probably there already; you remember how the story went. Before the PS3’s disastrous launch put things back into perspective, the complicated beginnings of the PSP had been Sony Computer Entertainment’s first mishap, at a time when the manufacturer seemed near invincible.

The console sold well in absolute terms, but it was sandwiched between two phenomena: the Nintendo DS, which inexplicably managed to be a cooler console for the general public despite its self-attributed toy-like nature, and then shortly afterwards the Apple iPhone, whose touch interface, always-on connection and, above all, Appstore were a much more relevant embodiment of the great multimedia ambitions Sony had for the Cross Media Bar and Universal Media Disc.

The situation improved around the end of 2006, particularly in Japan with the emergence of the social phenom Monster Hunter Portable, and to a lesser extent in the West with GTA Vice City Stories. In Japan, the console really took off in 2007, first with the release of Monster Hunter Portable 2nd in March and then, above all, with the release of the new PSP-2000 model, accompanied by Crisis Core Final Fantasy 7.

That means, between the end of 2004 and the end of 2006, for around two years, the PSP was a bit of a console for losers, with too few games, too many games that remained in Japan, too many games designed for home consoles but awkwardly adapted to the portable format, too many games geared towards Japanese otaku, poor hardware choices (the UMD, the absence of a second analog stick) and a wrong reading of the future by having completely missed the touch screen revolution. Suffice to say, that era of the PSP reminded me a lot of the Saturn.

I even remember precisely the announcement that made me compare the two consoles: it was the puzzle game Kuru Kuru Chameleon in January 2006, which made me think that it was exactly the kind of game that would have been released to general indifference on Saturn in 1997 before costing ¥10000 at Super Potato ten years later. (And it is a relatively expensive game today, at around ¥7000, but ironically, it’s its belated port to the DS that’s worth much more now).

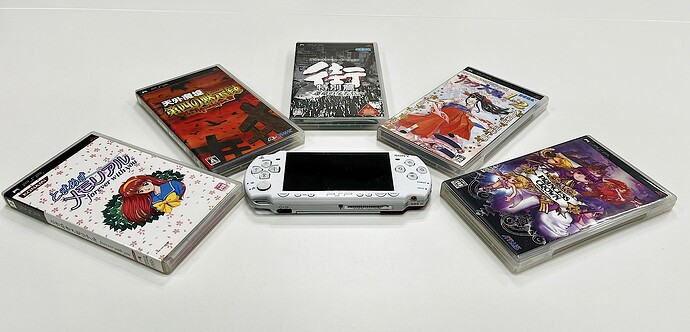

However, this hardware association wasn’t totally unfounded or subjective; it just so happens that six fairly emblematic Saturn games were released on PSP during this No Man’s Land phase of its career. There may have been others (I could have mentioned Myst, for example) and we can quibble about what counts as “a Saturn game”, but it’s these six titles that count for me. And they were all released only in Japan, which I find symbolic of the Saturn’s tragedy, but also of the PSP game library, which is probably still underestimated in the West today.

We’re talking about a time when Saturn emulation was very complicated, and Saturn ports to other consoles still very rare. This celebration of the Saturn concludes a few days too early to coincide with the 20th anniversary of the PlayStation Portable, on December 12, but I certainly won’t have the time or the same zeal for Sony’s little disc muncher, so we’ll celebrate it here instead, on November 30 (shut up), with the six games that sealed the peace between the Saturn and the PlayStation.

Here they are, in order of their release on PSP.

Princess Crown

11 December 1997

22 September 2005

The first game from (what was to become) Vanillaware, which already established their trademark for the next two decades: a side view action-adventure game with georgous sprites, a surprisingly developed setting and plot, memorable female characters and way too many food recipes.

The Saturn version had been a commercial failure and managed the feat of sinking two different studios (its first during development, then Atlus Osaka after release) before becoming one of the Saturn’s first “cult games” – and therefore expensive second hand copies – in the early 2000s, thanks in particular to the development of Internet message boards and the blossoming of more intellectual video game magazines and mooks like YūGē or Continue.

The PSP version changes virtually nothing. Vanillaware, which was then busy developing Odin Sphere for Atlus on PS2, wasn’t involved. This PSP version served three purposes for Atlus: it was their first game on the console, an opportunity to reap the rewards of the game’s recent critical and media reconsideration, and a promotional exercise for Odin Sphere, presented at the time as the spiritual successor to Princess Crown.

Shin Megami Tensei: Devil Summoner

25 December 1995

20 December 2005

Atlus’ second PSP game was once again a Saturn port, released in the week of its tenth anniversary. Unlike Princess Crown, Devil Summoner was a huge hit for Atlus on the Saturn. This was, of course, largely due to the fact that it was released on Christmas Day 1995, at the height of the console’s popularity in Japan, between the releases of VF2 and Sega Rally.

But 1995 was also arguably the peak of Shin Megami Tensei’s popularity. The RPGs in the series had been a monumental success on Super Famicom, but Atlus had the astute business intuition to move the series to Saturn and PlayStation at the best of times.

On Saturn, the series would keep satisfying its most hardcore fans with Devil Summoner (1995), a hardcore sequel/spinoff with a tougher challenge, weirder demons and (probably suiting the growing up of its early fans) a more adult setting, strongly inspired by manga and Hong Kong movies featuring hard boiled detectives navigating the underbelly of society. On PlayStation, the series took a different turn to appeal to a younger, broader audience, with Persona (1996), again launched at the right time, right when the general public decided to ditch the Super Famicom for the PlayStation.

Here again, the PSP version of Devil Summoner was released primarily to promote a new episode of Devil Summoner, Kuzunoha Raidō tai Chōrikiheidan, which would land on PS2 the following spring. At the time, in other words, the PSP was being treated by Atlus – and, indeed, by a number of other publishers – as a promotional stooge for bigger PS2 productions.

Devil Summoner on Saturn is also known for its fan disc, Devil Summoner Akuma Zensho, released four months after the game (until Atlus sold the two as a bundle from late Summer 1996). It was a kind of multimedia encyclopedia of the game’s demons, which were notoriously difficult to recruit in Devil Summoner.

Akuma Zensho is the kind of product “of its time” that would have come out as a guidebook two years earlier, but which testified to the popularity of the series at that stage, to the possibilities of the CD-ROM format compared to the cartridge format, and to the future multimedia ideal that Sega and the publishers were still imagining in 1995 for the Saturn generation of laser-based consoles. The content of Akuma Zensho is included directly inside the PSP version.

Sakura Taisen 1 & 2

27 September 1996 & 4 April 1998

9 March 2006

What have we come to when even Sega starts re-releasing Saturn games!? So, this is a rather 1:1 straight port of the first two games in the series, which was a bit of a disappointment for fans, as the first Sakura Taisen had at that point in time just received a nice remake on PS2, prefiguring what was to become the combat system of the Valkyria Chronicles series (developed by the same team).

Another problem: to fit the equivalent of five Saturn CD-ROMs on a single UMD, Sega had to make major concessions on sound quality and video scene compression, not to mention long loading times. Still, it’s an insane amount of content for a single UMD. You can choose to start Sakura Taisen 2 straight away, without having to finish the first one first.

Tokimeki Memorial ~Forever with me~

19 July 1996

9 March 2006

The most debatable fit on this list, since Tokimeki Memorial was originally a PC Engine game, and the ~Forever with me~ version was first released on PlayStation. Nevertheless, it remains one of the Saturn’s most emblematic games – and one of its biggest commercial successes – to the extent that the console received a number of spin-offs from this first episode alone.

But above all, Tokimeki Memorial released on the same day as Sakura Taisen 1+2; March 2006 is undoubtedly the paroxysm of the similarities between the two consoles. Too bad the Saturn never got its own Monster Hunter Portable…

As for the PSP game, it’s virtually the PS1 version as is, without any notable additions; it was officially released to commemorate the tenth anniversary of this version. Fair enough! You may have seen the news, but a new Switch version of the first Tokimeki Memorial was announced a few weeks ago.

Machi

22 January 1998

27 April 2006

Machi is a Sound Novel, in other words, an interactive photonovel in the style of a “game book” (a form of entertainment that was even more popular in Japan in the 80s than it was in the West). You follow a story, mainly reading pure paragraphs of text, making a few choices and navigating to an ending, and usually trying to solve a mystery.

Chunsoft is more or less the creator of the genre on consoles, first with the horror game Otogirisō (1992) and then more importantly the locked-room murder mystery Kamaitachi no Yoru (1994), a huge commercial success and even, one could say, a small social phenomenon at the time. These first two games were released on Super Famicom and launched an entire genre.

Machi is the third title in this series, and one of the last great Saturn games with its release in January 1998. In fact, its release on Saturn made little sense by that point – it was the perfect mainstream PS1 product for its time, and Machi would in fact be ported to PS1 a year later.

We owe Chunsoft’s apparent good grace to one of Nakayama Hayao’s last great moves before he stepped down as president of Sega. Noting that small Japanese developers were finding it increasingly difficult to deal with traditional publishers, and more and more keen to self-publish, and that the CD-ROM format greatly reduced the risks of game production for Sega compared to (e.g.) Nintendo’s cartridges, Nakayama had financed the creation of a support label for developer self-publishing, Entertainment Software Publishing (ESP).

ESP basically provided the distribution and promotion networks for the games, relying heavily on Sega’s structures, without having to go through an official production team at Sega. This commercial collaboration method attracted a number of “big” names, including Neverland (Chaos Seed), Treasure (Radiant Silvergun), Sting (Baroque), Game Arts (Grandia) and Quintet (Code R). If we were to consider ESP as a traditional publisher, it would undoubtedly be one of the best on the console.

Chunsoft didn’t need a structure like ESP to release its games: Machi is published by Chunsoft themselves, just to be clear. But as part of this charm offensive on smaller devs, and to counter Squaresoft’s support for PlayStation, Sega also approached Chunsoft to propose releasing more experimental stuff together.

We don’t know for sure whether Sega co-financed Machi, either via its own funds, a scam with ESP or another financial trick with its parent company CSK, but Sega has always been involved in Machi in one way or another, and this PSP release is a game published by Sega (and not Chunsoft).

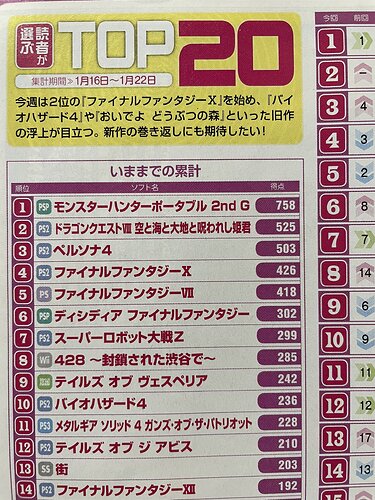

Machi had been a modest success on Saturn (~120,000 copies) without making much more waves on PlayStation (~60,000 copies), but the game truly became notorious thanks to Famitsu magazine and its weekly column 読者が選ぶTOP20 in which readers vote their twenty favorite games of the moment. For over a decade, Machi fans had organized themselves to constantly feature the Saturn version in this top. Here it is, chilling in thirteenth place in 2008, not far behind Metal Gear Solid 4 on PS3 and Tales of Vesperia on Xbox 360.

Such fervor from zealous fans because the game offers a unique narrative experience. We follow the intersecting fates of eight characters in Shibuya, each with their own independent storyline, and most of them never meet in the game. However, the choices made by the omniscient player influence the destinies of each character according to the actions committed for another character. So it’s not just a question of solving each character’s plot, but also of unraveling the puzzle that will lead to a happy ending for all the characters.

By now, you know the drill: Machi was re-released on PSP following renewed interest in the Saturn game, thanks to its vociferous fan base, and above all to pave the way for the promotion of a spiritual sequel, 428, which would eventually be released on Wii in 2008. Yet, symbolizing the changing status of the PSP in Japan, the PSP would eventually be entitled to its own port of 428, in 2009.

Tengai Makyō: Dai4 no Mokushiroku

14 January 1997

13 July 2006

Tengai Makyō Gaiden: Dai4 no Mokushiroku, which eventually lost its “Gaiden” a few months after its announcement, was the big RPG planned for the Saturn in 1996.

Developed in parallel with Tengai Makyō III: Namida (which famously ended up never releasing), the game’s title played on words to make it the unofficial Tenjai Makyō IV of the series; it’s still under this name (or its westernized Far East of Eden IV) that many talk about the game today.

Its planning studio Red had spread itself a little too thinly in 1996; they were simultaneously involved in the mediamix project Gulliver Boy, these two Tengai Makyō projects (plus Tengai Makyō ZERO had just been released in 1995) and that new Sakura Taisen game at Sega.

Announced as early as spring 1995, and repeatedly delayed, Dai4 no Mokushiroku (“the 4 (i.e. horsemen) of the Apocalypse”) was finally released at the beginning of 1997, barely escaping the ogre Final Fantasy VII, which would come out just two weeks later. Indeed, after Tengai IV, the apocalypse…

Namida and Dai4 no Mokushiroku had quite a challenge on their hands after the impact left by Tengai Makyō II: Manjimaru in 1992. It was no doubt this pressure, added to the cancelling of the original PC Engine version to restart development on PC-FX, a console quickly doomed to fail, that killed Namida. (Fun fact: Yoshida Naoki, of FF14 and FF16 fame, worked on Namida).

Dai4 no Mokushiroku did manage to release, despite a complicated final stretch of development. As the game was designed from the outset for the Saturn, it embraces even more openly the desire to mix JRPG with anime. We finally get real animated cutscenes, the enemies are drawn on cells and take up the whole screen during battles, and the game yaps a lot more. The overall vibe is also even more delirious and comedic than its predecessor, sometimes bordering on parody or pastiche.

Unlike all the other episodes, which take place in a feudal Japan as the Japanese imagined Westerners fantasized it in the 19th century (yep, quite a concept), this episode takes place in the American Wild West as a Japanese of the Shōwa years on acid might fantasize it thanks to Hollywood films. It’s less interesting from a “disguised critique of (Japanese) society” point of view, which I later came to understand better with Manjimaru, but it’s even wackier.

Dai4 no Mokushiroku is not the masterpiece that Tengai Makyō II was, and you can feel that the last arc of the story has been botched by delays, budget overruns and FF7 steamrolling its way to collision, but it’s still a great RPG.

Tengai Makyō III: Namida was finally remade from scratch and released in 2005 on PS2, almost like an unlikely remake of a ghost-game. To capitalize on the comeback of their most illustrious RPG series, Red and Hudson would (re)release the other three main episodes of the series in 2006, on three different consoles - which seems a rather stupid idea to me, but also testifies to the confusion among Japanese publishers circa 2004-2005 about the direction to take for their future.

Thanks to Microsoft’s blank checks, the Xbox 360 got a genuine (and much-needed) full 3D remake of the first game, Ziria. The Nintendo DS received a nice port of Tengai Makyō II: Manjimaru (worth a fortune today due to its modest print run), as its most mainstream episode but also a reasonable port of an old 2D game on a console with reasonable specs. As for the PSP version and its ambitions as a portable multimedia machine, it would logically be entitled to Dai4 no Mokushiroku, the most “interactive anime”-ish episode among the three.

Tengai Makyō: Dai4 no Mokushiroku is by far the best of these PSP ports. It’s basically the complete version of the game that Red and Hudson had hoped to release on Saturn.

This version adds two regions, densifies the ending and adds lots of little events to make the secondary characters more interesting. This nomad version also adds the possibility to save the game at any time, and the audio-video compression work is much more solid than that of Sakura Taisen. This is unquestionably the best version of the game, and also one of the best RPGs available on the PSP. ![]() You’re welcome!

You’re welcome!

![[PSP]Tokimeki Memorial - Fujisaki Shiori Speedrun in 47:01[WR]](https://f.insertcred.it/original/3X/6/4/6488d182356664ef0e1baec0b76958c5c49e948a.jpeg)

![[Présentation du jeu] Machi: Unmei no Kousaten Tokubetsu Hen (PSP)](https://f.insertcred.it/original/3X/8/2/82c94008debbba2eff32ec936f366a7629136fe8.jpeg)