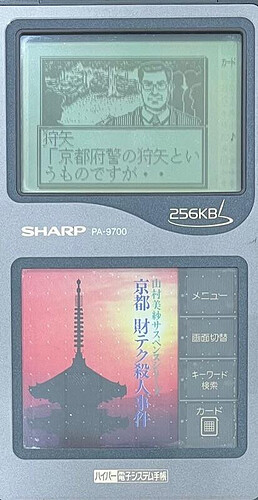

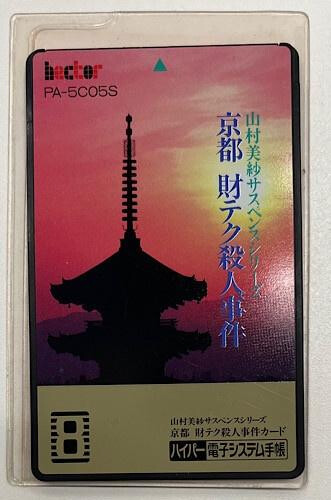

Here is our first game exclusive to the Hyper Denshi System Techō standard, which is kinda the SuperGrafX of the Denshi System Techō. I will elaborate on the hardware in the second half of this post but let’s focus on the game first.

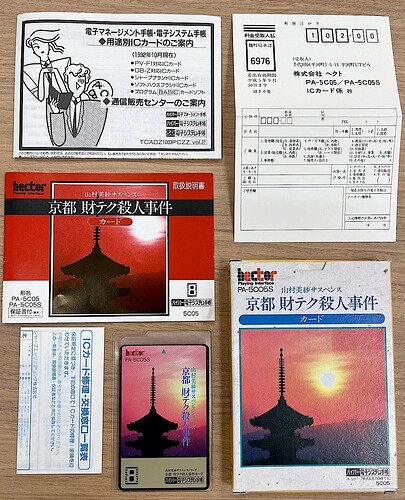

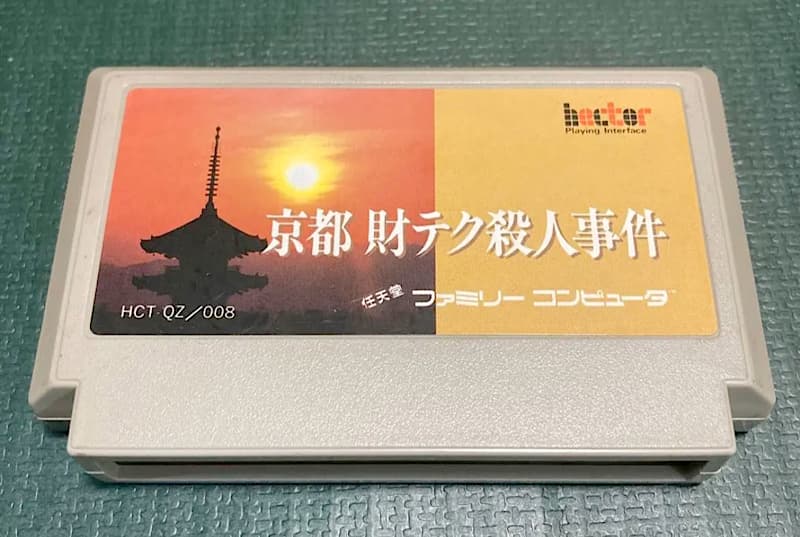

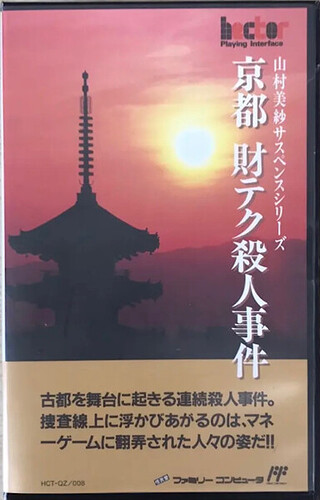

Yamamura Misa Suspense – Kyōto Zai-tech Satsujin Jiken (“The Kyoto Zai-tech Murder Case”) by Hector was originally a Famicom game, and one of those many detective adventure games derived from the smash hit Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken (→see Jeremy Parish’s excellent video retrospective for more context on its release and influence).

Following the success of Portopia, different publishers opted for the licensing of famous crime novelists to both secure a good story and capitalize on their fame to get noticed in the crowd of similar releases.

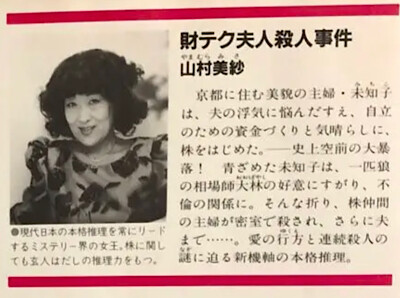

Irem went with Nishimura Kyōtarō (a prolific novelist who passed away last March) and Taito opted for Yamamura Misa, a female author specialized in “touristic” / “scenic” crime stories, all centered around the city of Kyōto and its most memorable sight-seeing spots.

Kyōto Zai-tech Satsujin Jiken was the third game in this specific series (apparently all developed by TOSE), and released in November 1990, a few weeks before the release of the Super Famicom in Japan. The genre was fading in popularity by then and that might be why Hector published this third episode instead of Taito. The game must have been scarcely produced because it is now one of the pricier Famicom cartridges in Japan. (I certainly gave up trying to get one in the preparation for this write-up.)

The story is original to the game, but takes inspiration from various Yamamura stories. In the Famicom version, your faceless and player-named avatar is an office lady and amateur sleuth who gets involved in solving the murder of a friend from her high-school days.

I’ll get to the rest of the plot a bit further down below but, first, I need to digress about the two Taito games that preceded Kyōto Zai-tech Satsujin Jiken – there’s an interesting payoff in sight, I promise you.

In the Taito games, the player avatar is also an original character, unique to that story. However, in both games, the protagonist is assisted in their investigation by Catherine Turner, a young, rich and beautiful blonde New Yorker who is one of Yamamura’s three great detectives (they are all female). In those games, she acts as the ever helpful sidekick made a trope of the Japanese mystery genre since Portopia.

Catherine is a freelance author / journalist working in Japan for some non-descript foreign press agency but, in her debut novel, she was just a visiting foreign student who also happened to be the daughter of the vice president of the United States! Oh my!

Catherine is unsurprisingly super wealthy; she basically would not need to work but enjoys being nosy and getting into trouble with cases that have nothing to do with her. She’s often seen taking advantage of her VIP status, using her “gaijin card” to circumvent expected Japanese manners or feign ignorance, and seeing her general bravado and wits solving the weird murder cases she constantly comes across.

Catherine’s a pretty interesting character considering she was created by a Japanese woman in the late Seventies, and became sort of a Girl Boss detective right smack into the pop culture trend of showcasing powerful (caucasian and mostly blonde) working women in Hollywood during the Eighties. I think there’s a whole feminist angle to these novels and indeed to this game that I am probably not the best equipped at tackling, but feel free to dig into that topic further on your own free time.

Although he does not appear in every novel, Catherine’s usual “Watson” is Hamaguchi Ichirō, a no-nonsense straight man (in all applicable ways) who was initially a brillant university student tasked by his principal to become Catherine’s escort / bodyguard / translator, due to her sensitive VIP status.

Obviously, there is a romance aspect to their odd couple dynamic: she’s both infuriatingly brazen and wicked smart, he’s boringly down to earth but wiser than her and always reliable. They quickly become an item in the books, but always with a hint of will they / won’t they (get serious and marry) to keep some tension going.

It is also important to explain that Catherine and Ichirō’s relationship, from a detective novel aspect, is much more balanced than the traditional tropes of the master detective and their assistant. Apparently, Ichirō often outsmarts Catherine and generally has a better sense of how to traditionally proceed with a police investigation, even if it is Catherine who usually ends up being the ace solving each affair.

I am sorry to go “The guy who has only seen Boss Baby” on y’all but, based on my short research, their couple dynamic really strongly reminds me of Suzumiya Haruhi and Kyon and I am now personally convinced Yamamura’s books have had a strong influence on Tanigawa Nagaru’s work.

In the Famicom version of Kyōto Zai-tech Satsujin Jiken, a big departure from the Taito-published episodes is that Catherine does not appear at all in the game. Both the player avatar and her improvised assistant are just young women from Kyoto trying to solve their friends’ murder. Note that the original character in the first two games was more gender-neutral but, in Kyōto Zai-tech Satsujin Jiken, you are explicitly playing as a young woman. I am not sure how many adventure games had already offered that situation by 1990.

Anyway, I suspect this casting choice was heavily criticized at the time of the Famicom version’s release, because one huge change (improvement?) of the Denshi System Techō version is that now you play as Catherine herself, despite most of the plot and many of the dialogues being the same as the Famicom version.

I assume it was indeed much simpler for TOSE and Hector to retroactively turn the protagonist into Catherine rather than to make her the assistant (given that your friend is helpful but clearly not much smarter than you and definitely not a wealthy foreign journalist).

Nevertheless, I would guess people who had not played the Famicom version probably wondered why Catherine didn’t rely on Ichirō or another regular friend from the novels as her sidekick. I also suspect some of Catherine’s characterization in the game betrays the identity swap, but I’ll leave that judgement to true Meitantei Catherine fans. Let’s get back to the story.

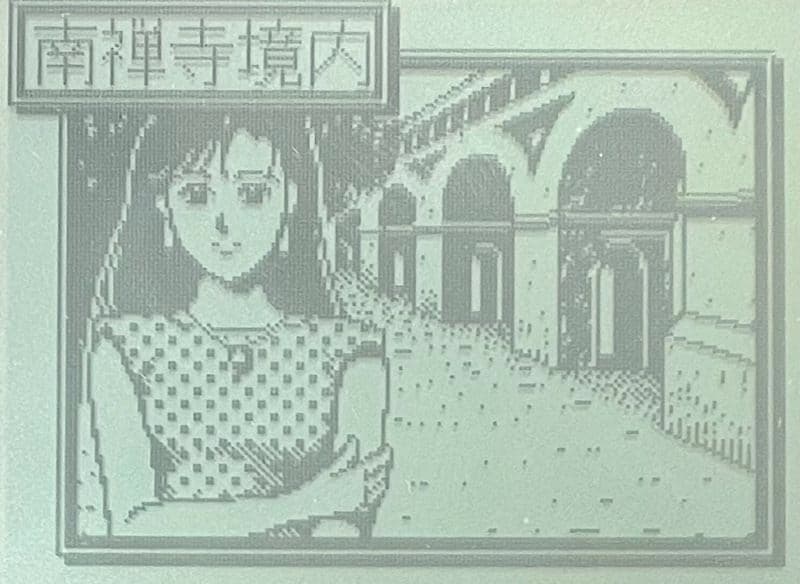

Set in the scorching Kyōto summer, the game starts as a young office lady Catherine is meeting up with two high-school friends on a lazy Saturday afternoon, near the Nanzen-ji’s famous aqueduct, for Tanabata.

{wait, I thought Catherine arrived in Japan during college? Err whatever}

Natsuko, a budding TV actress and this game’s sidekick, is already here with you but your friend Yumiko is uncharacteristically late. She had been admitted to Tokyo University (= she is very smart and headed for a promising career) and then proceeded to join an elite pharmaceutical company back in Kyoto, so its not her style to miss an appointment and oops she’s dead. You barely get a second to check her corpse and surroundings when Inspector Kariya arrives on the scene and nothingtoseeheres everyone.

{Kariya is pretty much the Inspector Lestrade of the Catherine series, so it was a cool cameo in the Famicom game but it now makes zero sense that he would not already know Catherine. But I’ll stop here with this kind of remark, you got the point.}

Pretty quickly, you’ll figure out that the mystery of Yumiko’s murder is linked to some insider trading scandal involving her pharmaceutical firm. That is pretty topical: in early 1990, right at the burst of the economic bubble, the Japanese financial world was hit with a wave of insider trading scandals.

The Zai-tech mentioned in the game’s title is a term which became popular in mainstream media around that time, referring to the speculative financial investments using the support of computers (財務テクノロジー zaimu technology) which arose after the 1984 deregulation of the Japanese financial market under the pressure of the U.S. government.

I have read some reviews (for the Famicom version, obviously) complaining that this game, past the introduction at Nanzen-ji, misses the usual “local charm” of Yamamura’s novels by barely making use of Kyoto’s unique appeal. Indeed, the story is largely a corrupt big firm affair which could have happened in any other city. But at least, the plot was admirably topical when the game initially came out.

Another cool surprise about this version is that it fleshes out the story and especially the first scenes wonderfully. There is, to my astonishment, a full guide for the Famicom version on GameFAQs but you would not be able to progress in the Denshi System Techō port if you followed it blindly. Several scenes were added, for the better as far as I can tell, to flesh out some relationships and improve some transitions in the story, such as giving better context to how you figured out some relationships, or how you found certain clues.

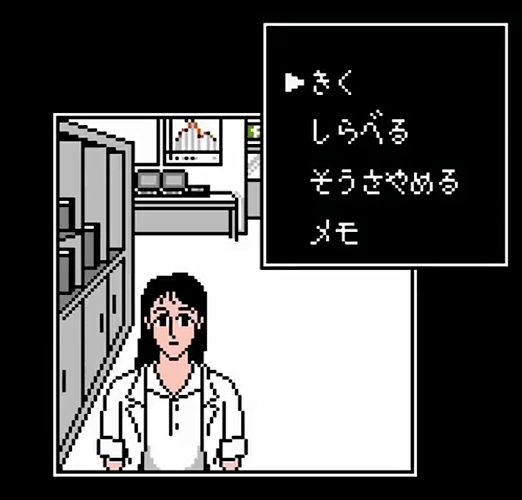

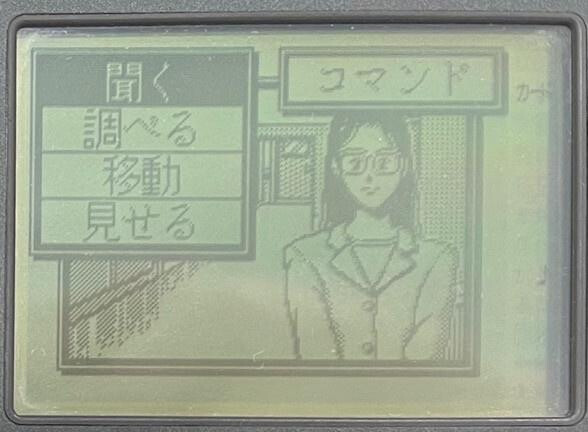

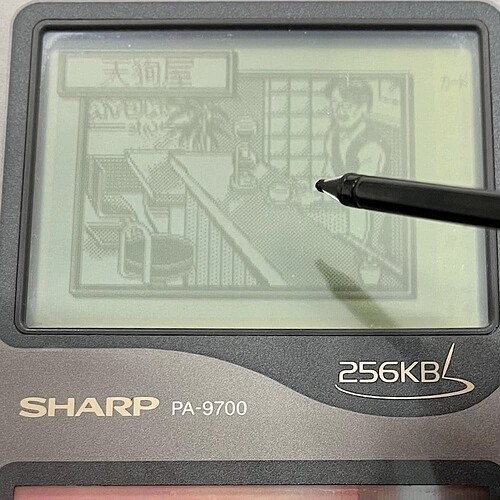

Another frequent complaint regarding the Famicom version is that it looked slightly worse than the two Taito games, with pretty simple graphics and weak-ass art direction for a 1990 game. Here again, the Denshi System Techō version is unarguably a glow up, both technically and stylishly.

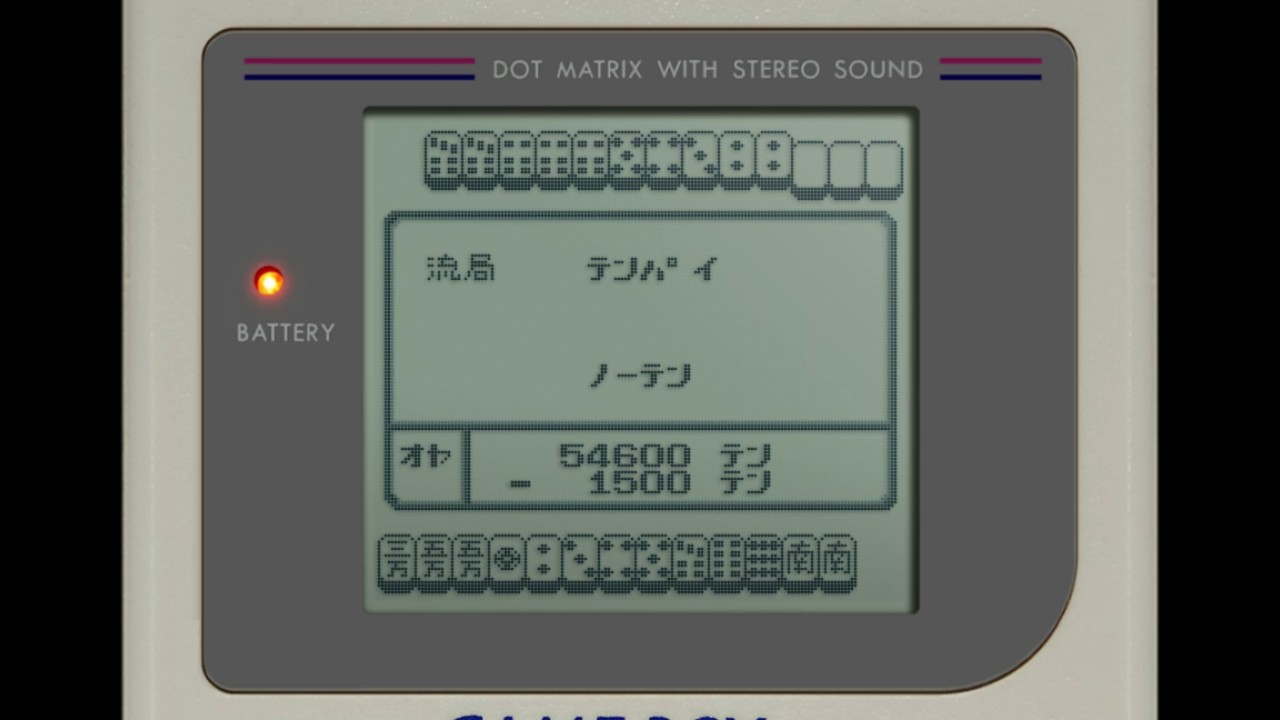

Not only that, but the Denshi System Techō features full kanji and katakana support, making the text much more legible than the Famicom version (provided you get a good view of the non-backlit, cheap DMG screen).

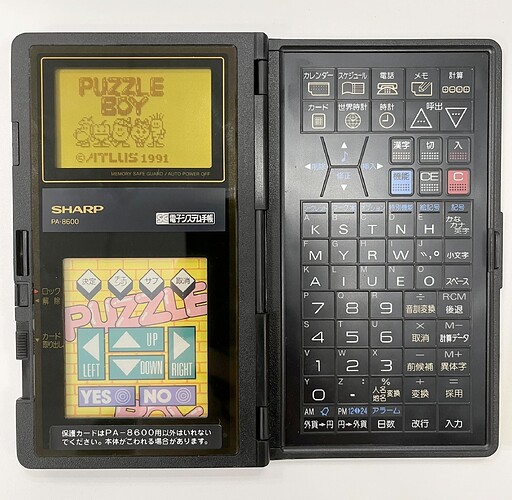

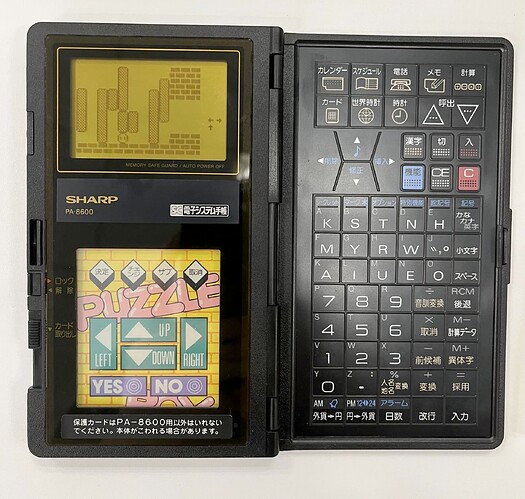

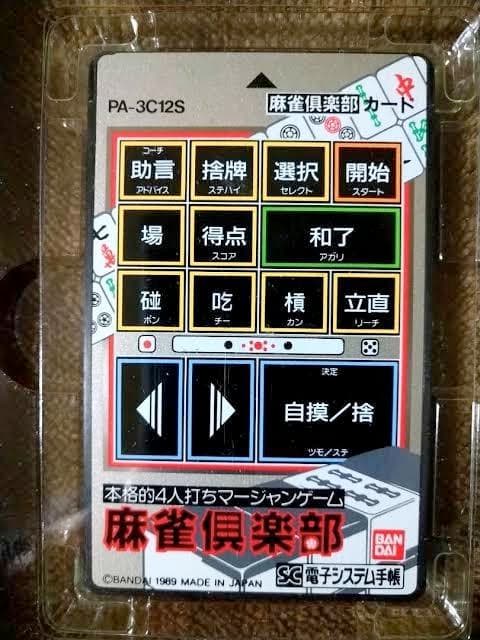

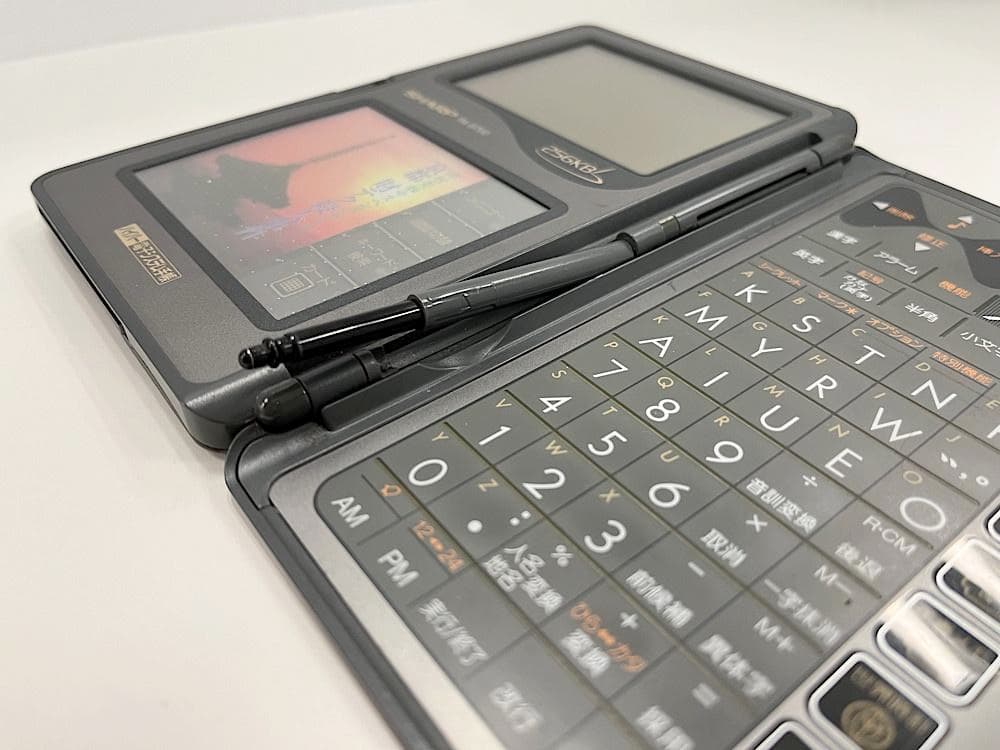

<pEven better: the game is fully compatible with Denshi System Techō machines featuring a touch screen! So instead of awkward controls or menus, you can directly tap on the screen and choose your actions, and investigate items shown on screen. Nintendo DS-style ! In 1991!

So far, I have introduced games which have largely been compromised compared to their closest equivalent on Famicom or Game Boy. Kyōto Zai-tech Satsujin Jiken for the Denshi System Techō is not only better than the Famicom version, it also blows out of the water any adventure game on the Game Boy until maybe… Tokimeki Memorial Pocket in 1999? This 1991 game feels like playing something from the WonderSwan era.

So what’s happening here, and what’s up with the “touch screen compatibility” that I had never mentioned in a Denshi System Techō game until now? Let’s talk about hardware. Let’s talk about the Hyper Denshi System Techō.

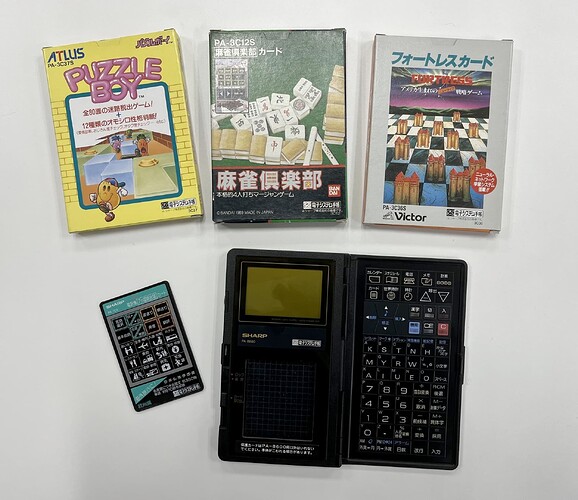

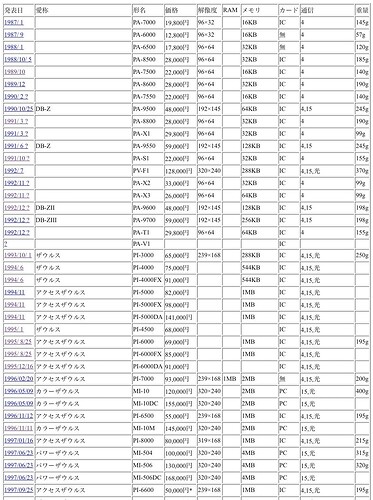

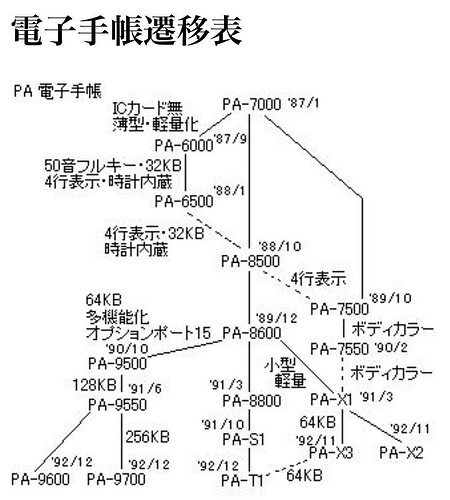

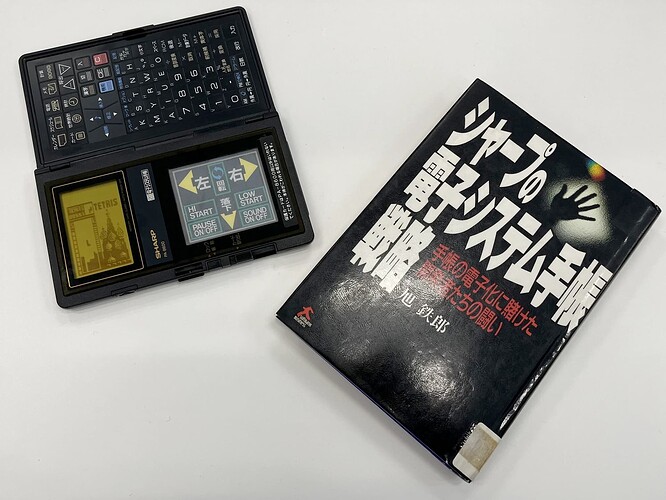

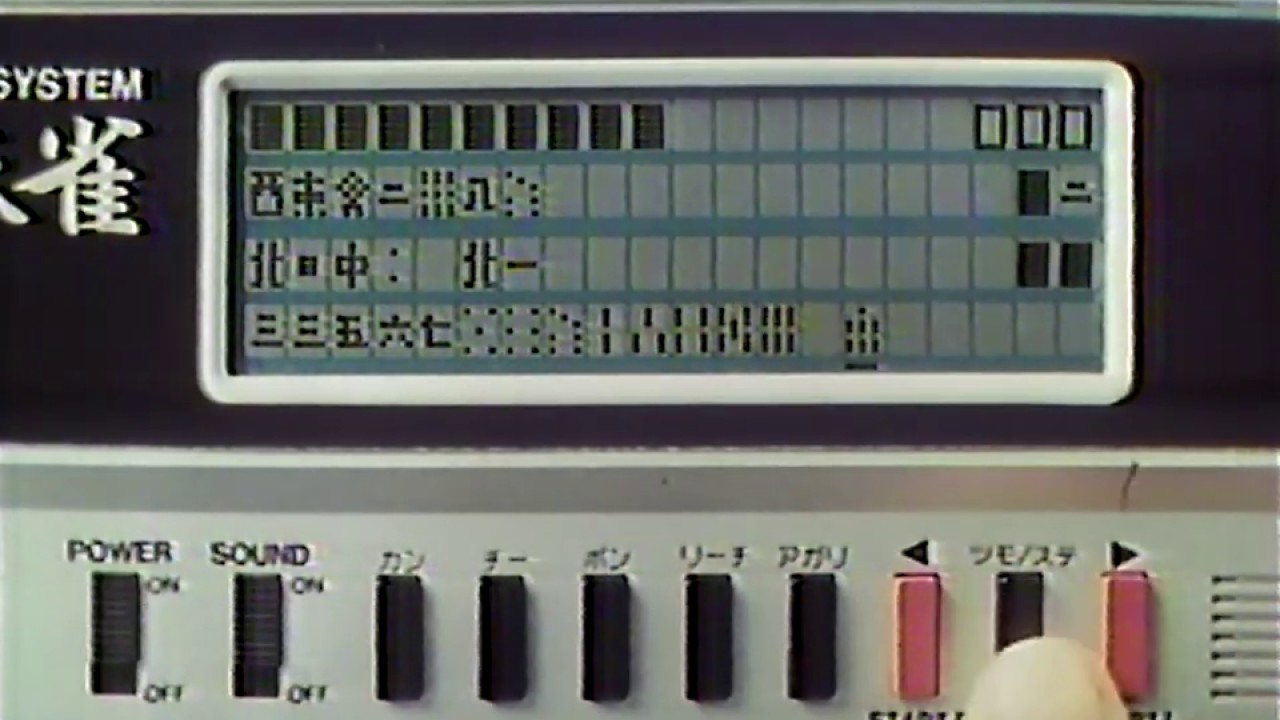

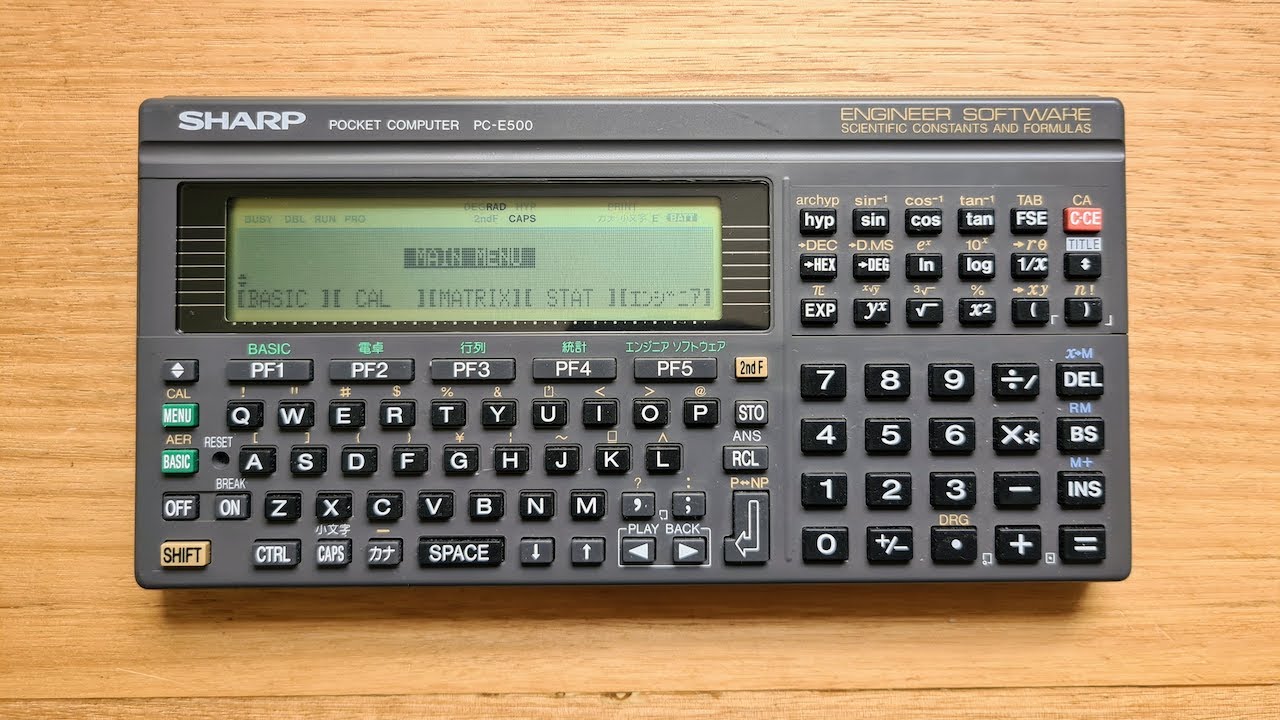

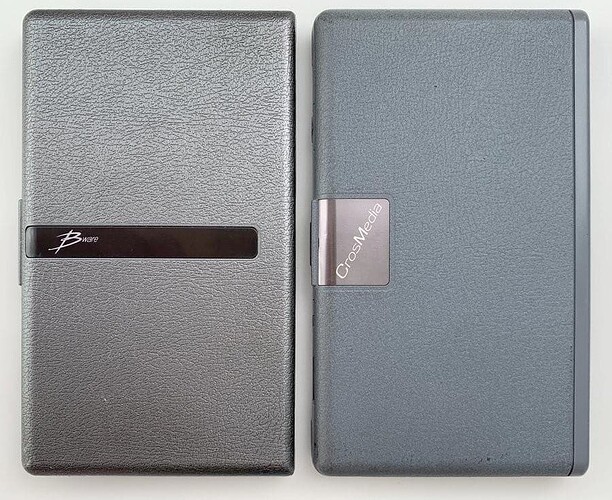

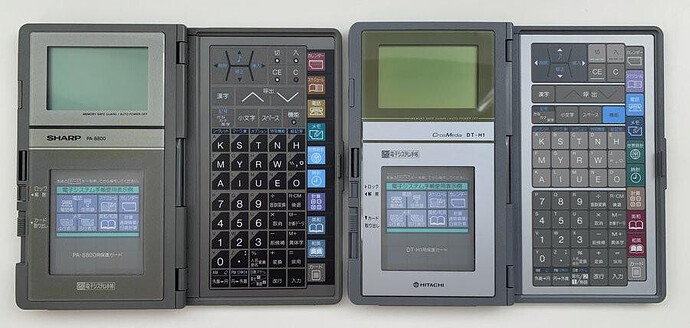

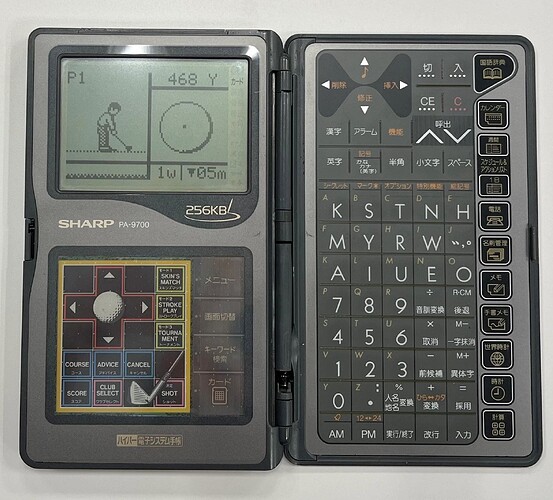

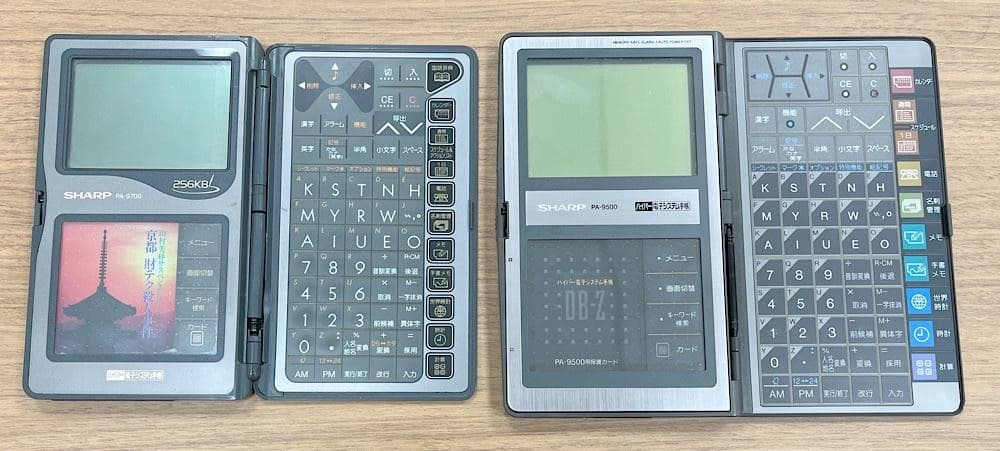

Released in 1990, the “DB-Z”, also known as the PA-9500 (it’s the right one on the picture above), was the first model to feature the Hyper Denshi System Techō logo, highlighting its superlative specs. Sharp encouraged publishers to release their own cards taking advantage of that new hardware, and some software from the Denshi System Techō library is only compatible with Hyper Denshi System Techō machines.

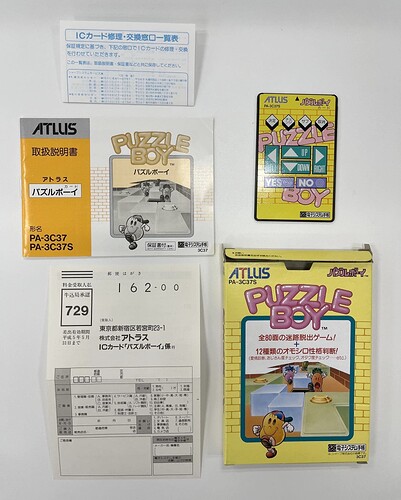

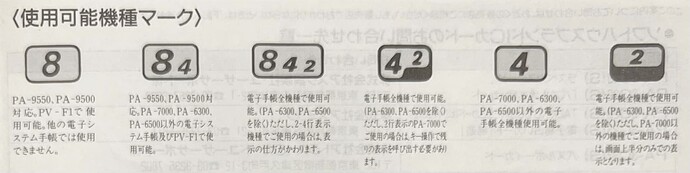

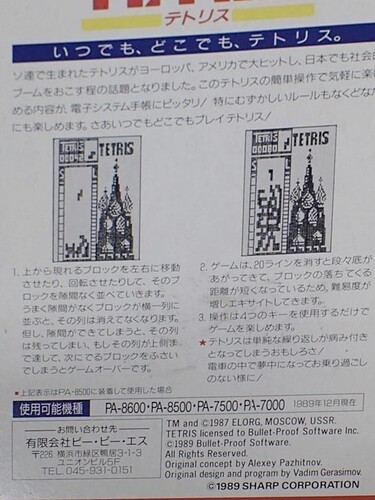

We have already discussed some games which were not compatible with the original PA-7000 earlier in this thread. As the compatibility exceptions grew, Sharp established a compatibility icon standard to help out consumers figure out on what machine each software could be played or not.

Refer to the newly edited second post of this thread for a detailed explanation of these icons, including what the digits mean, but in summary:

① The Hyper Denshi System Techō models can play any card.

② Cards with the 8~4 symbol run better on the Hyper Denshi System Techō models.

③ Cards with the 8 symbol run only on the Hyper Denshi System Techō models.

As of the writing of this post, I have identified seven 8 cards and two 8~4 cards among all the games released between 1989 and 1992. That’s not a lot, but it would indeed put the Hyper Denshi System Techō on par with the SuperGrafX catalogue, so…

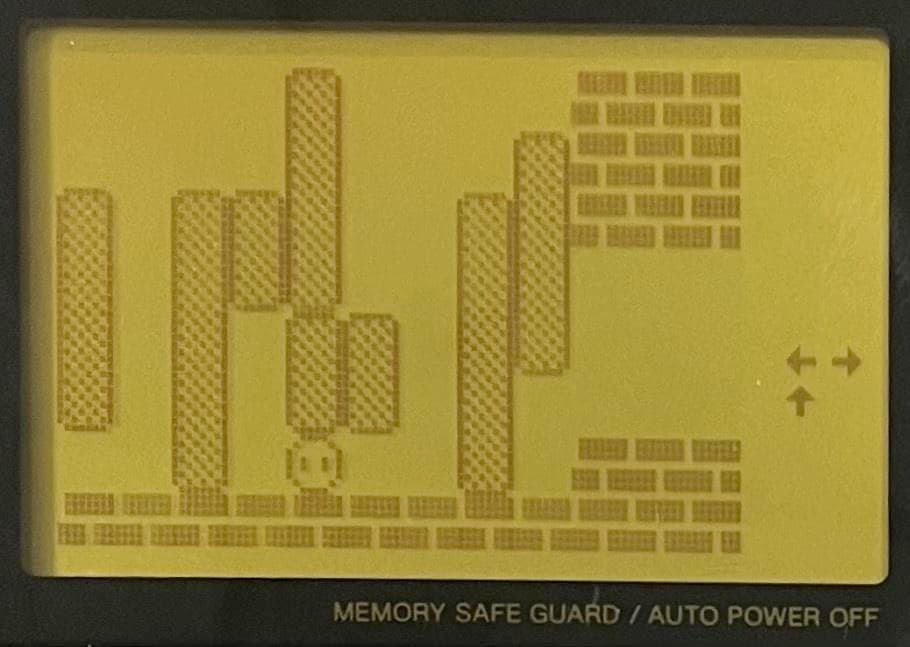

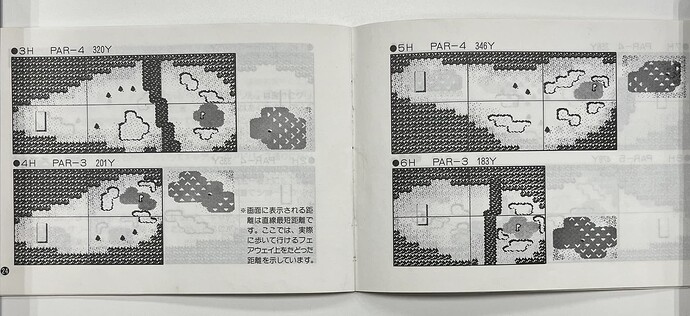

Games exclusive to the Hyper Denshi System Techō could benefit from a minimum screen size of 192×145, far above the standard 96×64 available to most games. By comparison, the Game Boy (all the way to the Game Boy Color) was stuck with a 160×144 screen, and the WonderSwan used a 224×144 screen.

In terms of memory, the Hyper Denshi System Techō jumped to a minimum RAM of 128KB (256KB for some models), instead of 8KB for the Game Boy, 32KB for the Game Boy Color and 64KB for the WonderSwan.

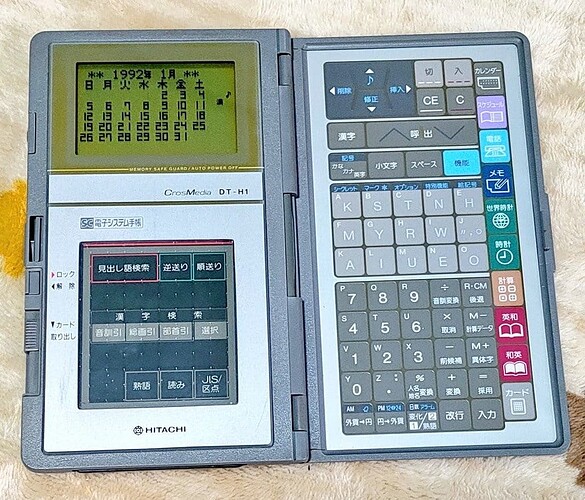

As mentioned above, the Hyper Denshi System Techō models also included a resistive touch screen, pretty much the same tech as a Nintendo DS, and even had their own tiny stylus.

Once again: This machine came out in 1990! Kyōto Zai-tech Satsujin Jiken came out in 1991! We’d only get the Nintendo DS in November 2004!

(A Nintendo DS also cost three times less at launch than a DB-Z, to be fair.)

On the PA-9700 which has been used for my review, the stylus can be slotted back cleverly within the inner hinge of the machine via a pivotable sheath, which is frankly not super convenient in practice, but pretty cool.

The remaining issue is that the Hyper Denshi System Techō models still did not include any form of proper sound chip, so this port of Kyōto Zai-tech Satsujin Jiken does not feature the soundtrack of the Famicom version.

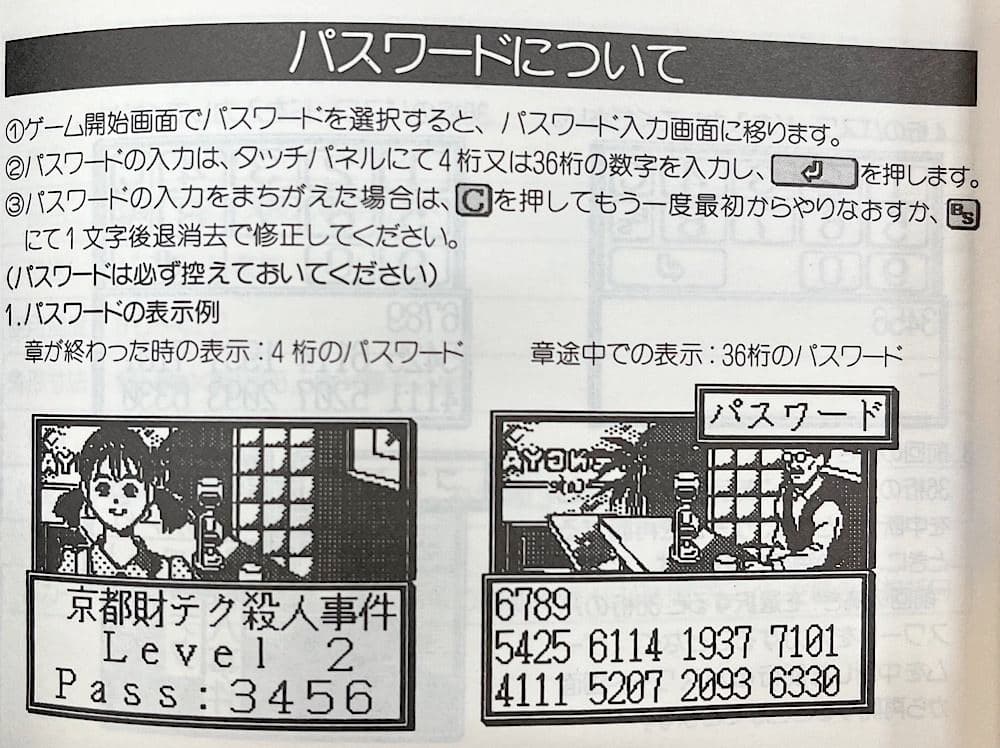

Another hurdle you may be wondering about is saving your progress. Based on my experiments, as long as you keep the IC card in your Denshi System Techō, the game stays in a sort of sleep mode when you turn the machine off or leave the game to check one of its OS-level features.

If you do remove the card, there are two options available to you. You can restart from a specific chapter in the story, which involves a simple 4 digits password, or you can visit your friendly café owner and request a longer 36 digits code to save exactly where you are. Not the most convenient, especially in an era without smartphones to take a quick screenshot of the code, but serviceable.

Besides these two hardware-inflicted hurdles, Yamamura Misa Suspense – Kyōto Zai-tech Satsujin Jiken is pretty much the crown jewel of this part-time gaming system, as far as I can tell.

Unfortunately, by the time Hector’s game came out, it was probably clear that Sharp’s dream of establishing a new software standard had failed. Japanese adults were indeed buying these clever and expensive electronic organizers, but they were not really indulging in the whole IC card swapping and collecting bit that could have unlocked a bunch more interesting ports like this one.

Incidentally, this weekend marks the first anniversary of this thread!

- I am going to get pretty busy in the coming weeks/months so I am not sure when is the time and fitting topic for the next update, but maybe I’ll combine a few shorter reviews of games that don’t deserve a thorough exposé on their own.

![]() 手帳 techō) and Filofax-like pocket organizers (

手帳 techō) and Filofax-like pocket organizers (![]() システム手帳 system techō) even included a case to store and carry one of these practical pocket calculators along with you.

システム手帳 system techō) even included a case to store and carry one of these practical pocket calculators along with you.