I can’t contain my excitement. I kind a complete OED for 28 dollars. Its exterior is in bad repair but it’s spine and signatures are intact.

I read this short story last night by Iraqi Israeli author Samir Naqqash. I don’t have anything intelligent to say about it at the moment, but I enjoyed it a lot and it’s given me a lot to chew on.

I think many of you would enjoy it.

I’m considering getting his first novel, published in English for the first time in 2018.

Dang, too bad about the L&R book. I found a copy on eBay for $10 which I might get anyway just for the family tree/relationship chart.

This urth.net site is as cool as the book

I finished Who’s Afraid of Gender? at a fairly leisurely pace and very much enjoyed it; I was afraid it would be too dense for me to fully comprehend, but it was surprisingly approachable. Don’t have much more to say on it.

And then I was possessed for some reason and read Wilder Girls in a single day. This one was a recommendation from a friend and man…this did not come together the way I was hoping. There was a lot of promise in what the author was putting down in the first half of the book, but as we start to uncover the causes behind the mysterious illness mutilating and taking the lives of so many girls, it honestly falls apart in a wild mess. It was quite readable even with some more unconventional prose style appearing midway through–and I did like what the author was attempting here–so I guess that’s why I took it out in a single day.

Finished Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Dafoe this morning. I picked this one up off the strength of The Storm, which I quite enjoyed. Though Crusoe is not a journalisitc account of a historical event like The Storm is, Dafoe seems similarly obsessed with presenting the narrative as the journal of a real living person and contemporary of the reader. I find it very enjoyable to pick apart the delicate balance between a grounded, epistolary recounting of events and the narration of a compelling story with a lot of dramatic moments.

Overall, I found reading this very fulfilling, perhaps more so because I had no expectations as to the quality or nature of the book save that it was about a castaway in a deserted island.

Evidently a lot has been written and said about this book which imo proves how well it encapsulates different themes: the complex social relations of colonialism in the 1600s, individualism and religion. I am just now digging through the many things that have been said about this book as an economic novel. This article has been a rewarding read so far. All in all, it is great to have read a book I knew not much about beforehand, and find that it intersects so well with discussions and concepts I’m generally interested in.

On the other hand, I am glad I started with the “hard” part which is reading the primary text, which unlocks the ability to read what has been said of it with a more informed perspective. Mostly I like having the full picture as sometimes other authors are keenly focused on just one part of the whole.

Despite the potentially problematic or myth-like recounting of Crusoe’s gradual ‘colonization’ of the island, I found myself quite enjoying the way Dafoe narrates Crusoe learning how to plant crops, practice husbandry and stuff like that. Not unlike the satisfaction of succeeding in a survival game (Minecraft is a Robinsonade, change my mind).

I have too many quotations that I could probably paste here (thanks to Libby for letting me export those into an html file, goated app). So I will just include a couple, so *spoilers ahead.

One of the most interesting through-lines of the book is how Crusoe was able to successfully thrive in this deserted island for 28 years. By the time he was rescued, Crusoe had a number of goats, steady supply of grapes, corn and rice, as well as two fortifications with several rooms and pots for storage. Crusoe at this point begins giving himself the title of governor or patriarch of the island. This starts when the only other sentient beings there were his domesticated animals (he had not seen any sign of humanity since the shipwreck):

It would have made a Stoic smile to have seen me and my little family sit down to dinner. There was my majesty the prince and lord of the whole island; I had the lives of all my subjects at my absolute command; I could hang, draw, give liberty, and take it away, and no rebels among all my subjects. Then, to see how like a king I dined, too, all alone, attended by my servants! Poll [his parrot], as if he had been my favourite, was the only person permitted to talk to me. My dog, who was now grown old and crazy, and had found no species to multiply his kind upon, sat always at my right hand; and two cats, one on one side of the table and one on the other, expecting now and then a bit from my hand, as a mark of especial favour.

Shortly afterwards is when Crusoe first comes into contact with a sign that there are other human beings on the island.

It happened one day, about noon, going towards my boat, I was exceedingly surprised with the print of a man’s naked foot on the shore, which was very plain to be seen on the sand. I stood like one thunderstruck, or as if I had seen an apparition. I listened, I looked round me, but I could hear nothing, nor see anything; I went up to a rising ground to look farther; I went up the shore and down the shore, but it was all one; I could see no other impression but that one. I went to it again to see if there were any more, and to observe if it might not be my fancy; but there was no room for that, for there was exactly the print of a foot - toes, heel, and every part of a foot. How it came thither I knew not, nor could I in the least imagine; but after innumerable fluttering thoughts, like a man perfectly confused and out of myself, I came home to my fortification, not feeling, as we say, the ground I went on, but terrified to the last degree, looking behind me at every two or three steps, mistaking every bush and tree, and fancying every stump at a distance to be a man. Nor is it possible to describe how many various shapes my affrighted imagination represented things to me in, how many wild ideas were found every moment in my fancy, and what strange, unaccountable whimsies came into my thoughts by the way.

The appearance of a footprint of the shore was legitimately unsettling to read. Moments like these are what kept me interested in the story of the book, outside of any philosophical interpretation of what is going on.

At the time many in Europe believed in the presence of a cannibalistic people inhabiting the islands of the Caribbean (specifically the Carib peoples). Crusoe believed that the footprint belong to a cannibal, which led him to increase his fortification and began to consider plotting a plan of defense against them. Surprisingly, Crusoe has this train of thought:

These people had done me no injury: that if they attempted, or I saw it necessary, for my immediate preservation, to fall upon them, something might be said for it: but that I was yet out of their power, and they really had no knowledge of me, and consequently no design upon me; and therefore it could not be just for me to fall upon them; that this would justify the conduct of the Spaniards in all their barbarities practised in America, where they destroyed millions of these people; who, however they were idolators and barbarians, and had several bloody and barbarous rites in their customs, such as sacrificing human bodies to their idols, were yet, as to the Spaniards, very innocent people; and that the rooting them out of the country is spoken of with the utmost abhorrence and detestation by even the Spaniards themselves at this time, and by all other Christian nations of Europe, as a mere butchery, a bloody and unnatural piece of cruelty, unjustifiable either to God or man; and for which the very name of a Spaniard is reckoned to be frightful and terrible, to all people of humanity or of Christian compassion; as if the kingdom of Spain were particularly eminent for the produce of a race of men who were without principles of tenderness, or the common bowels of pity to the miserable, which is reckoned to be a mark of generous temper in the mind.

Another through-line that I am sure is rich in how it can be reinterpreted/critique is Crusoe’s relationship with Friday, which begins once Crusoe saved Friday from being eating by cannibals.

After he had slumbered, rather than slept, about half-an-hour, he awoke again, and came out of the cave to me: for I had been milking my goats which I had in the enclosure just by: when he espied me he came running to me, laying himself down again upon the ground, with all the possible signs of an humble, thankful disposition, making a great many antic gestures to show it. At last he lays his head flat upon the ground, close to my foot, and sets my other foot upon his head, as he had done before; and after this made all the signs to me of subjection, servitude, and submission imaginable, to let me know how he would serve me so long as he lived. I understood him in many things, and let him know I was very well pleased with him. In a little time I began to speak to him; and teach him to speak to me: and first, I let him know his name should be Friday, which was the day I saved his life: I called him so for the memory of the time. I likewise taught him to say Master.

Crusoe, at this point embodying the role of english colonizer, freely chooses to allow or deny Friday his own subjectivity. He sometimes treats him as an equal, other times he is referred to as a mere ‘creature’.

One last thing, it appears that at the very end, Crusoe ends up owning the island he was deserted in:

In this voyage I visited my new colony in the island, saw my successors the Spaniards, had the old story of their lives and of the villains I left there; how at first they insulted the poor Spaniards, how they afterwards agreed, disagreed, united, separated, and how at last the Spaniards were obliged to use violence with them; how they were subjected to the Spaniards, how honestly the Spaniards used them - a history, if it were entered into, as full of variety and wonderful accidents as my own part - particularly, also, as to their battles with the Caribbeans, who landed several times upon the island, and as to the improvement they made upon the island itself, and how five of them made an attempt upon the mainland, and brought away eleven men and five women prisoners, by which, at my coming, I found about twenty young children on the island.

Besides this, I shared the lands into parts with them, reserved to myself the property of the whole, but gave them such parts respectively as they agreed on; and having settled all things with them, and engaged them not to leave the place, I left them there. From thence I touched at the Brazils, from whence I sent a bark, which I bought there, with more people to the island; and in it, besides other supplies, I sent seven women, being such as I found proper for service, or for wives to such as would take them. As to the Englishmen, I promised to send them some women from England, with a good cargo of necessaries, if they would apply themselves to planting - which I afterwards could not perform. The fellows proved very honest and diligent after they were mastered and had their properties set apart for them. I sent them, also, from the Brazils, five cows, three of them being big with calf, some sheep, and some hogs, which when I came again were considerably increased.

Anyways, those are some instances where I think insight or discussion can be drawn from the way these things are developed during the book.

My other reason to read this book came from my desire to revisit Friday, or the Other Island by Michel Tournier, which from what I can tell recounts/reinterprets the story from the perspective of Friday. I read a part of this book at a bookstore once and it stuck with me despite not reading the original. Now I can go back and find out what it’s all about. There’s also Foe by J.M Coetzee which looks interesting, and will likely be my first Coetzee read.

Edit:

cw: discussion of slavery

one thing I forgot to hone in on a bit more is that Crusoe’s journey to Africa and South America puts him in contact with the transatlantic slave trade. it’s treated as matter-of-factly but is mentioned so often that I think it is a salient concept in discussions of the book.

First, Robinson having settled in Brazil and given a plantation to manage, soon sees great success but is then requested to accompany a ship to Guinea in order to acquire slaves:

[…] three of them came to me next morning, and told me they had been musing very much upon what I had discoursed with them of the last night, and they came to make a secret proposal to me; and, after enjoining me to secrecy, they told me that they had a mind to fit out a ship to go to Guinea; that they had all plantations as well as I, and were straitened for nothing so much as servants; that as it was a trade that could not be carried on, because they could not publicly sell the negroes when they came home, so they desired to make but one voyage, to bring the negroes on shore privately […]

I am not sure as to the particularities of how this trade was handled in Brazil, or why Crusoe’s trip had to be clandestine as this passage implies. Nevertheless, Crusoe at this point was a successful plantation owner who was himself interested in the acquisition of slaves. Upon his rescue from the island (which is not really a rescue I should say – Crusoe’s escape was narrated as being due to his strategic approach to negotiating and comandeering a group of about 12 castaways like himself) Crusoe returns to Brazil and fully becomes both a slave-owner and owner of his own little colony. I think that the interpretation of Crusoe by economists, and the disucssion of a “Crusoe economy” is interesting to analyze knowing these key aspects of who Crusoe is as created by Dafoe. I studied economics and I was very put off by this sort of thing:

(from wikipedia):

Robinson Crusoe is assumed to be shipwrecked on a deserted island.

The basic assumptions are as follows:[4]

- The island is cut off from the rest of the world (and hence cannot trade)

- There is only a single economic agent (Crusoe himself)

- All commodities on the island have to be produced or found from existing stocks

There is only one individual – Robinson Crusoe himself. He acts both as a producer to maximise profits, as well as consumer to maximise his utility.[5] The possibility of trade can be introduced by adding another person to the economy. This person is Crusoe’s friend, Man Friday. Although in the novel he plays the role of Crusoe’s servant, in the Robinson Crusoe economy he is considered as another actor with equal decision-making abilities as Crusoe.

Not sure what to call it, but it is akin to washing out the power imbalances in the name of rationalizing a set of economic decisions. Note the reference to Friday as Crusoe’s friend. Based on my reading of the article I mentioned before, this seems to provide fertile ground for a Marxist critique/interpretation.

excellent post. i’ve never read robinson crusoe, but i certainly want to now. when i was younger, one of my favorite books was my side of the mountain and i’d reread it over and over. i wonder if rc would tap into that same feeling.

i was going to do a round up post of the books i’ve read lately but you’ve raised the bar.

sounds about right

From: Robert King bobking@gate.net

Subject: Re: (urth) Casting Call

Date: Wed, 13 May 1998 01:17:50And in honor of the all the Last Episode hooplah, we could have the Seinfeld version, with Jerry as Severian, of course.

The others could be:

Jonas: George

Dorcas: Elaine

Dr. Talos: Kramer

Baldanders: Newman

Vodalus: The Soup Nazi

Thecla: “Mulva”

The Autarch: J. Peterman

Father Inire: The Maestro

Abdiesus: George Steinbrenner

I think I’ll stop there.

Thank you :).

Robinson Crusoe has abundantly detailed descriptions of him learning how to make a boat, bake bread, making ceramic pots, charcoal, etc. There are several notable sections where he reflects on his past life, his previous disbelief in God (he began reading the Bible every night), stuff like that. However it felt sparse, which I found interesting. There are much more words spent on describing manual labor than a description of intense feeling of longing for human connection.

I’ll also say that Crusoe’s connection to the natural world of his island is mostly in the context of husbandry and his taming of it, from plants to animals. This differs from the imo more ‘spiritual’ aspects of isolating oneself in nature that I enjoyed Upstream by Mary Oliver.

I’d still recommend Robinson Crusoe though!

(I added a small section to the end of my original post, too much to talk about with this book lol)

I got similarly invested in Robinson Crusoe after reading it; it’s not only an interesting novel on its own terms, but the way it so clearly reflects the attitudes of that era of English/European history, as well as how influential it was on later writers/economists/philosophers gives it an additional dimension.

I recorded a video a few years ago comparing Robinson Crusoe with the Herman Melville novel Typee that you might find interesting. If you’ve never read Typee, I’d recommend it as a good counterpoint, telling a similar sort of tale from a different yet related perspective and time period (flawed in its own ways.)

was checking to see if used copies Polyphemus had dropped in price (fat chance) and learned that it actually got a whole new edition not long ago

Never heard of this book, but it seems cool. Thanks for shouting it out.

some of the books i’ve read recently which are coincidently pre-war german language –

little snow landscape - robert walser

walser is in my pantheon, so luckily there’s always a slow drip of new translations from nyrb and likeminded publishers. walser, for those who don’t know, was a bit of an enigmatic character in world literature. he was contemporaries with kafka, and in fact even predated him a bit (kafka wrote letters praising walser). he had novels and some stories published, but never reached great success. he bounced around the swiss-german region of the country, mostly following his brother around and writing his strange, strange literature. he never married and was likely a virgin.

when he was older, he checked himself into a few mental asylums ala the magic mountain. there, he told people he gave up writing. he kept writing, actually, but in secret on tiny scraps of paper in his own microscript. these microscripts of which there are hundreds and other pieces he wrote throughout his life are fiction, but they’re strange little fragments that are both whimsical and deadly serious. to describe them would to belie their magic, but many pieces are about picking flowers, going to a beer garden and listening to music, watching the moon out the window, or seeing children smile.

a little snow landscape is just more of these as yet untranslated pieces. i have to admit i wasn’t as enraptured by this book as his others, but i’ve honestly had a bit of a hard time reading lately in that i find my mind elsewhere as my eyes scan the page. it could also be the translator’s fault. either way, flipping through the book know i see that i dogeared many moments of brilliance.

motley stones - adalbert stifter

another contemporary of kafka. kafka also admired stifter, calling him “my fat brother.” for most people, that should be enough to buy this book immediately.

stifter is apparently well-known in germany (@FishHead confirm?), but in america is only ‘known’ (i.e. translated) for a story called rock crystal, which i’ve read a few times. sebald and other writers i admire have mentioned stifter, so i was excited when i found out this book was getting translated. it included a brief biography, and stifter’s life made me a little sad. he pined for a noble woman, was refused her as a commoner, entered into an unhappy marriage with an uneducated woman, failed to have children but did lovingly foster a niece who died in childhood by drowning in a river, had critical opinion turn on his work, then fell into an illness induced stupor during which he picked up a nearby razor and slashed his throat during a final moment of brief lucidity.

the stories themselves are absolutely beguiling. they’re idyllic, but there’s a darkness lurking at the edges. the darkness can sometimes be natural, like a hailstorm or house fire, but it can sometimes be supernatural like a fairy tale. they’re technically clean and masterful, but they also feel naive as if someone knows the truth of the world but refuses to admit it to themselves. the closest analogy i can think of would be those early century landscape paintings you see in the american wing of any museum. they are the work of master draftsman, but they also have an odd distortion. they are beautiful, but they are raw. they also have a touch of the anonymous about them, as in the focus is strictly on the work:

the lord chandos letter - hugo von hofmannsthal

this is one of the best books i’ve read in a long time. whereas walser and stifter had a touch of the quaint, hofmannsthal was downright menacing. the stories had the gothic romanticism of poe, but were impressionistic and had the cadance of poetry.

hofmannsthal was a well-to-do wunderkind of the viena scene in the early 1900’s. i think he was between 19 and 26 when he wrote these stories and was even an accomplished poet beforehand. he eventually had a crisis of artistry, stopped writing these singular works of art and instead became a milquetoast librettist because he thought works of popular art were the best way to enlighten the masses. he seems to be thought of as a wasted genius.

after reading this book, i can see why. i used “beguiling” already in this post, but it’s apt to use here, as well. there was a contemporary rhythm in these stories in that they felt like a half-rabid dog breathing down my neck in real-time. there is something spectral in these stories. there is a love for the world in them, but one that is fleeting and aware of it’s smallness.

one of favorite moments in this book was a series of three scenes: a solider recalls a childhood memory of a milkmaid drowning herself in a raintub; the solider was the one who discovered her later that night when he came across her legs draped over the side of the barrel; a battleworn horse is numb to all sensation so it dumbly eats a bushel of oats as yellow maggots crawl between it’s teeth; the same solider from earlier reaches for a silver pocketwatch out of habit but is once again reminded of it’s absense–it was stolen by his only friend, a fellow solider who was now camped in a different city. i found those events so visceral and touching that will stick with me in my long time.

i would gladly read anything hofmannsthal wrote, so until i buy a $50 hardcover of his selected writings, this will remain a unique little gem. the titular story is available online.

Hello @MoH, Insert Credit Forum’s resident German FishHead here, reporting live from the scene.

Jokes aside, I had not heard of Stifter before your post. I’m not bold enough to claim that people I don’t know are also not well-known by the general public so I looked into him a little.

He doesn’t seem to be part of the general German class curriculum in schools from what I could gather. One German Radio Prague article from 2014 introduces him with “Nowadays he’s mostly known to a small circle of literature lovers, mainly in Austria and Germany”. I found a list of 18 German (and 6 Austrian) schools named after him. With one exception they are mostly located in the southern half of Germany (Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg). He also lends his name to a couple of streets, for example in Munich.

The impression I get from what I read is that he was more relevant and well-known in the past, especially in the area close to his original home (roughly enclosed by the triangle formed by connecting Bavaria, Czechia and Austria) but has fallen a bit out of fashion and isn’t commonly known by the general public anymore.

I bet things are different if you went to one of the aforementioned schools. I, for example, remember learning about Adolph Schönfelder in elementary school because my school was named after him but people from other areas of Germany probably don’t know of him.

The article mentioned above is quite interesting because it talks about Stifter through the lens of Kazuhiko Ogawa, a Japanese German studies professor who seems quite enamored with Stifter’s work. According to him Stifter is part of all German studies courses in Japan. It also mentions that around that time Stifter was being somewhat rediscovered by people from the Czech Republic.

I always find it super interesting to see the differences between a countries’ view of itself (be that by the general public or academically) and the foreign view on a countries’ culture. Here in Germany I feel like this difference can be especially big because after world war 2 there has been a lot of estrangement from a lot of older cultural works. Either because the artists played a controversial role during the nazi regime or because the works had been used heavily by the nazis to build a sort of German mythology.

I feel like that sort of distancing is good and necessary in a lot of cases but also does a disservice to a lot of “innocent” art and artists that suffer from the amorphously unsettling feeling a lot of Germans get when they look at old German art.

And with that, back to the studio.

fascinating, huge thank you for the research. how did you find out what schools were named after him? i’d be curious to see how many schools we had in america were named after authors. on a whim, i found a steinbeck elementary in california, though i can’t imagine we have many. the only streets we have named after authors outside of ceremonial renaming are those you might find in the bleak “themed” subdivisions.

i’m curious to know what authors are considered canon in germany as in read by most high schoolers but still respected by literary types. also, what’s the view of foreign authors who write in german, such as the swiss or austrian, are they widely read in germany or are they viewed as more specialist literature in the way translated books are? i’m also also curious to know what innocent authors you think suffer from the post-war distancing.

so many questions…

I was going to wait until I finished this book before saying anything about it but I just finished a particular brutal and fantastic 20 page session toward the last quarter of the book I Who Have Never Known Men and felt like I had to sing its praises immediately.

It’s a book from 1995 by Belgian author Jacqueline Harpman and is inspired by her and her family’s experience fleeing Belgium when the Nazis started invading. The basic premise is 40 women are in a bunker, under 24/7 surveillance by three patrolling guards, and none of them remember how they got there. The narrator is one of the women and was a very young child when she was put in the bunker so she has effectively known nothing but life on there. The book is very mysterious but is largely uninterested in the mystery of the hows and whys of the situation. It’s more focused on how these women deal with the situation at hand and how the narrator grows over time. The prose is very plain and matter-of-fact which makes the way the story is told feel really unique to me. It’s a short book but still find time to linger on the right things.

I have been very affected by it and think it’ll surprise people, as it has me!

speaking of Michael Shea’s Polyphemus another out-of-print-hard-to-find-now-legendary novel likewise got a reprint not long ago: Notice by Heather Lewis. I thought it was really quite good, and I did not much care for The Second Suspect which this book is a kind of reworked telling of, without the crime procedural structure around it. Heads up it’s a very Content Warning experience. The affect is distressingly blank and colorless in places. Not sure exactly what to compare it to, but some of those non-Maigret Simenon novels that have this quiet pathology to them. Notice is about a sex worker’s parasuicidal efforts in parallel to being preyed-upon by abusers and her murky attempts at finding and providing kindness , which is very affecting. Recommended to grown adult readers (call it 35+ to be safe)

fascinating, huge thank you for the research. how did you find out what schools were named after him?

Glad to be of service! I searched for “Adalbert Stifter Schule” and found a list of schools with that name on Wikipedia. A school in Fürth claims that there are 600 schools with his name in Europe but I couldn’t find any source that confirms that, just the archive.org record of the page making the claim. (I didn’t look very hard though)

i’m curious to know what authors are considered canon in germany as in read by most high schoolers but still respected by literary types.

I think there actually aren’t many books that get read at schools but aren’t respected in literary circles. Some exceptions might be books that are very much written for school kids but even then they’re not really scoffed at. In general I feel like the books we read in school were always read through the lens of “This is a book that was written at a certain time under certain circumstances and is reflective of a larger trend at that time. Let’s think about that.” There was very little “This is what literature should be!” if you know what I mean.

Germany has a relatively complex school system so I can’t speak for the experience of everybody but I went to a Gymnasium, which is meant to prepare students for higher education at a university. German literature was taught mainly from two angles:

- Forms of literature like ballads, novellas, novels, plays/dramas, short stories etc. For each form a selection of well-known and defining works got selected, read and discussed. Usually in combination with the second angle.

- Eras or movements of German literature (called “Epoche” in German). These eras were discussed chronologically if I remember correctly and usually roughly in-sync with our History lessons.

Here’s a probably incomplete list of authors and works I can remember having read for school (completely or in parts) categorized by the literary movement whose lens we have discussed them through:

Oh god this list became much longer than I thought

Pre-Modern:

- Enlightenment

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (Nathan the wise)

- Sturm und Drang

- Friedrich Schiller

- Intrigue and Love

- The Pledge

- Goethe

- Faust

- The Sorrows of Young Werther

- Erlkönig (ballad)

- Friedrich Schiller

- Romanticism

- Joseph von Eichendorff (Various poems)

- Novalis (Various poems)

- E.T.A. Hoffmann (Various poems)

- Brothers Grimm (I don’t remember what but I’m almost certain we read something from them in school)

- Young Germany and Vormärz

- Heinrich Heine

- Georg Büchner (Woyzeck)

- Realism

- Theodor Fontane (Effi Briest)

- Theodor Storm (The rider on the white horse)

Modern and Post-Modern:

- Modern

- Rainer Maria Rilke (Poems)

- Hermann Hesse (Steppenwolf)

- Impressionism

- I could swear we read some impressionist stuff but I can’t remember any of it

- Expressionism

- Franz Kafka

- Metamorphosis

- The Process

- Short stories

- Franz Kafka

- Exile-literature and literature written during the war

- Thomas Mann (Buddenbrooks)

- Post-war

- Max Frisch (Homo Faber)

- Bertolt Brecht (The threepenny opera)

- Post-modern/contemporary

- Patrick Süskind (The Perfume)

- Günter Grass (The Tin Drum)

- Rafik Schami (A hand full of stars)

- Juli Zeh (Corpus Delicti)

- Juli Zeh seems to be a relatively new addition to modern literature in schools. Corpus Delicti seems to be the book of hers that usually gets talked about from what I gathered. I read that book as an adult and I liked it.

Friedrich by Hans Peter Richter is a book that we read in school but which I wouldn’t expect to be particularly highly respected by literary types. I guess it was chosen more because it talked about the holocaust in an approachable way and also showed its horrors. I found it very moving as a teen but I haven’t read it since.

also, what’s the view of foreign authors who write in german, such as the swiss or austrian, are they widely read in germany or are they viewed as more specialist literature in the way translated books are?

From my experience there isn’t a big distinction between how I (or my friends and family) view German authors versus non-German authors writing in German. In general if you would ask me to list German authors I would subconsciously translate that to “authors that wrote in German”. I think that’s also true for the general public. Sure, we usually are aware whether an author is from Austria, Switzerland or Germany but usually that doesn’t have too much of an impact on how we read or perceive a book. Except when it heavily influences the story and the book makes a big deal out of being set in Vienna for example.

In general a lot of - especially contemporary - books don’t read all that differently because they’re usually written in Hochdeutsch (literally “High German”) which is a standardized version of the language. And while there are differences between German, Austrian and Swiss Hochdeutsch they are very much mutually intelligible and as such read more like dialects than anything else.

For example I’m from northern Germany and as such reading a book by an Austrian author might not feel more or less exotic than reading a book by a Bavarian author who leans into their dialect.

Case in point: I listed both Hermann Hesse and Rainer Maria Rilke in my list of canon German writers, who are both swiss and austrian respectively.

When it comes to spoken language on the other hand… let’s just say if a Swiss or Austrian person does not want me to understand them they could easily lean into their dialect and my untrained ears would be lost. The same goes for some areas of southern Germany as well though.

i’m also also curious to know what innocent authors you think suffer from the post-war distancing.

I didn’t have any specific authors in mind when I wrote that, sorry. It’s more that we learn a lot - and I really mean a lot - about the holocaust in school. And because history and german classes get taught quite interconnectedly a lot of the negative associations from german history get entangled with the “old” literature we experience at the time. So there’s always a certain gravitas associated with older German literature whether it is directly connected to the holocaust or not. And that basically makes reading “the classics” somewhat unattractive to a lot of people. Which really is a shame, I think. I also found myself reading a lot of literature from other countries and kind of avoiding German works of the more literary variety for that reason. Although I’m intending to actively work against that. (Ironically I haven’t read a single book by German author since I got my library card so yeah… I’m still working on it, haha)

so many questions…

No worries, this is a fun exercise in self-reflection for me! It’s always interesting to see one’s culture through a different lens. For a lot of this I never even really thought about how somebody outside of the Swiss-Austrian-German cultural sphere would feel about these things.

got myself a couple of interesting books

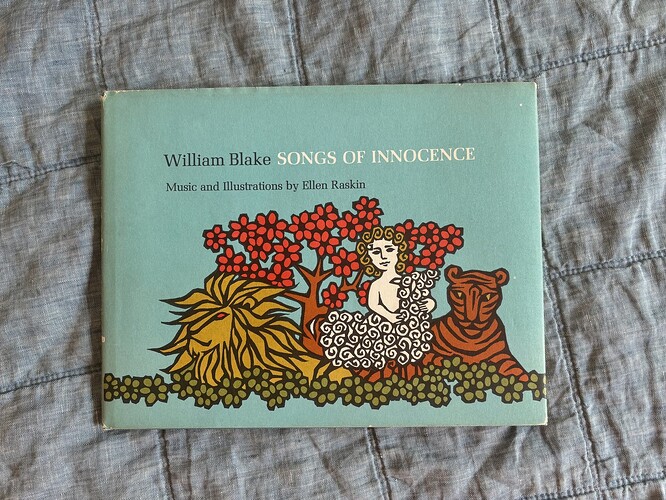

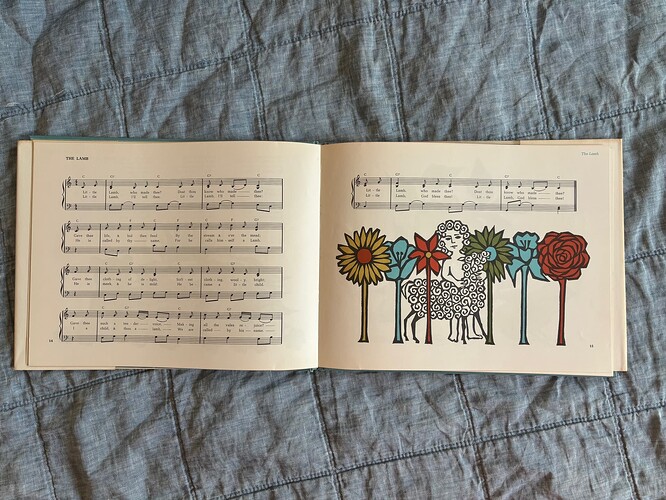

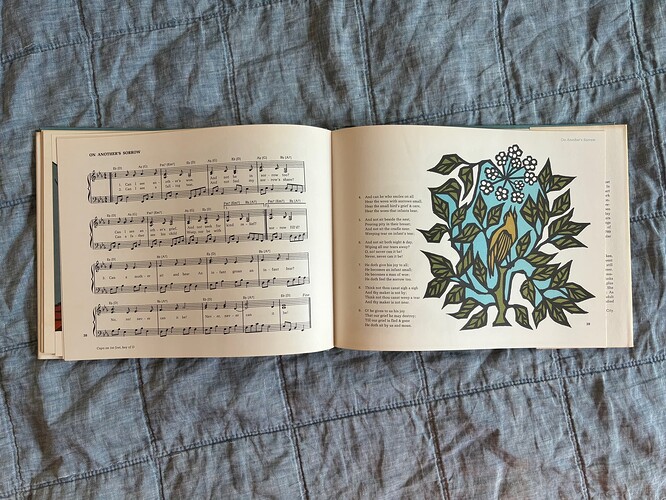

Ellen Raskin’s woodcut illustrated and also musically annotated edition of Songs Of Innocence doesnt look like Experience got the same treatment unfortunately. Wonder if the music is good

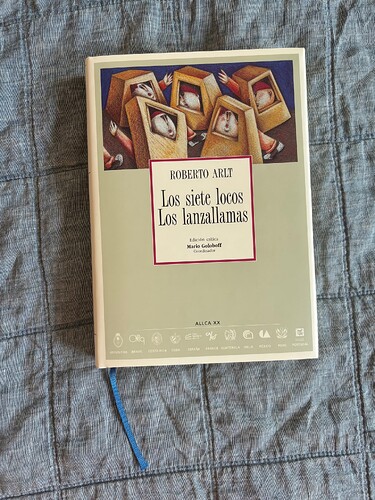

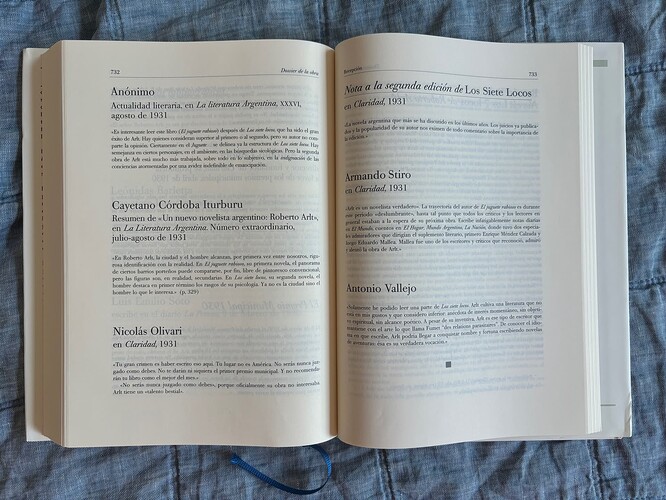

And also picked up the Alción Edición Crítica mentioned earlier itt of Los siete locos and Los lanzallamas bc it looked cool. And sure enough it’s a luxury vehicle kind of book.

There’s probably 500 pages of critical writing included alongside the (meticulously preserved and annotated) primary texts. Extremely impressive feat of scholarship in addition to being like an immaculate physical object. A++ job.

And ok those “can’t spell” allegations vs Arlt snopes dot com we have to rate as partially true lol. But who really cares.

@Bonsai don’t know if you’ve had a chance to tackle this volume yet, but it collects a number of those contemporaneous critical reactions you were curious about

Really a wonderful book I gotta say. Would be eager to pick up more from the series, although they’re expensive new and even more so on the used market so will have to be selective to say the least. What a lineup though (weird, old website you have to scroll to the bottom and click “Catálogo” to see the whole series)